Article published on 30 August 2025.

Interview: HBM – Photo credits: © A. Certain / Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris

In this second Paris chapter, Cristiano Ferraris, associate professor and curator of the mineralogy collection at the French National Museum of Natural History, connects the royal past to today’s challenges. He advocates for rekindling young people’s passion for knowledge, driven by a clear conviction: understanding minerals means shedding light on our daily lives and preparing for the future.

To start, could you introduce yourself to our readers and walk us through the key stages of your background?

My name is Cristiano Ferraris. I’m an associate professor in mineralogy at the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris, and since 2009 I’ve been in charge of the mineral and gem collections.

My journey began in 1990. I initially set out to become an engineer -I dreamed of airplanes and aerospace. But I quickly realized that it wasn’t my way of seeing world. Science was a constant presence at home: my father was a professor of crystallography at the University of Turin, and my mother taught natural sciences at the high school level in our native Piedmont region, in Italy. So I turned toward geology and enrolled at the University of Turin.

I completed my studies in 1995, followed by a brief interlude: I was put in charge of sealing the Somport tunnel, which connects France and Spain through the Pyrénées. The following year, I began my PhD in Fribourg, Switzerland, which I completed in 1999. I then received a postdoctoral grant in Siena, Tuscany, and spent several years in Singapore.

In 2004, I heard about an opening for a associate professor position at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. At the time, I even had to look up what “maître de conférences” meant… I passed the competitive exam in October 2004 and took up the post in April 2005. After a year at the museum, I returned briefly to Singapore as a visiting professor, then came back for good in January 2009, right in the middle of renovation work on the Gallery of Mineralogy and Geology, where we’re standing today.

Without going into too much detail, I’ve also had the chance to do some fieldwork: assignments on drilling platforms and occasional work as a geologist in active mines. These were brief but formative experiences, both scientifically and in the field.

So how does one become a mineralogist after studying geology? In Italy at the time, the first two years of university were generalist. After that, students chose a specialization. Mine was metamorphic rocks, specifically, high-pressure rocks. Northern Italy, and especially the lower Aosta Valley, is ideal for that: it’s the region of the eclogites.

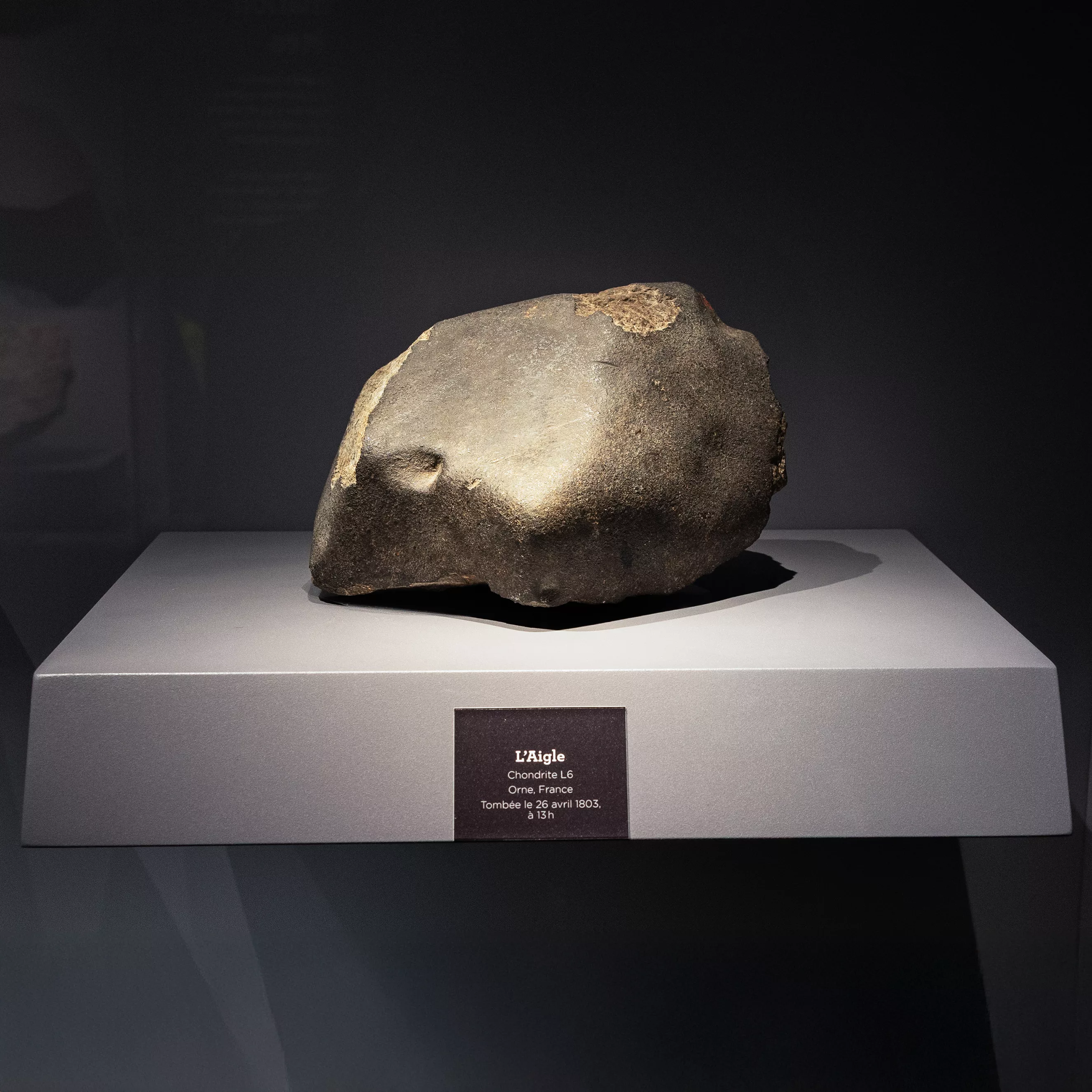

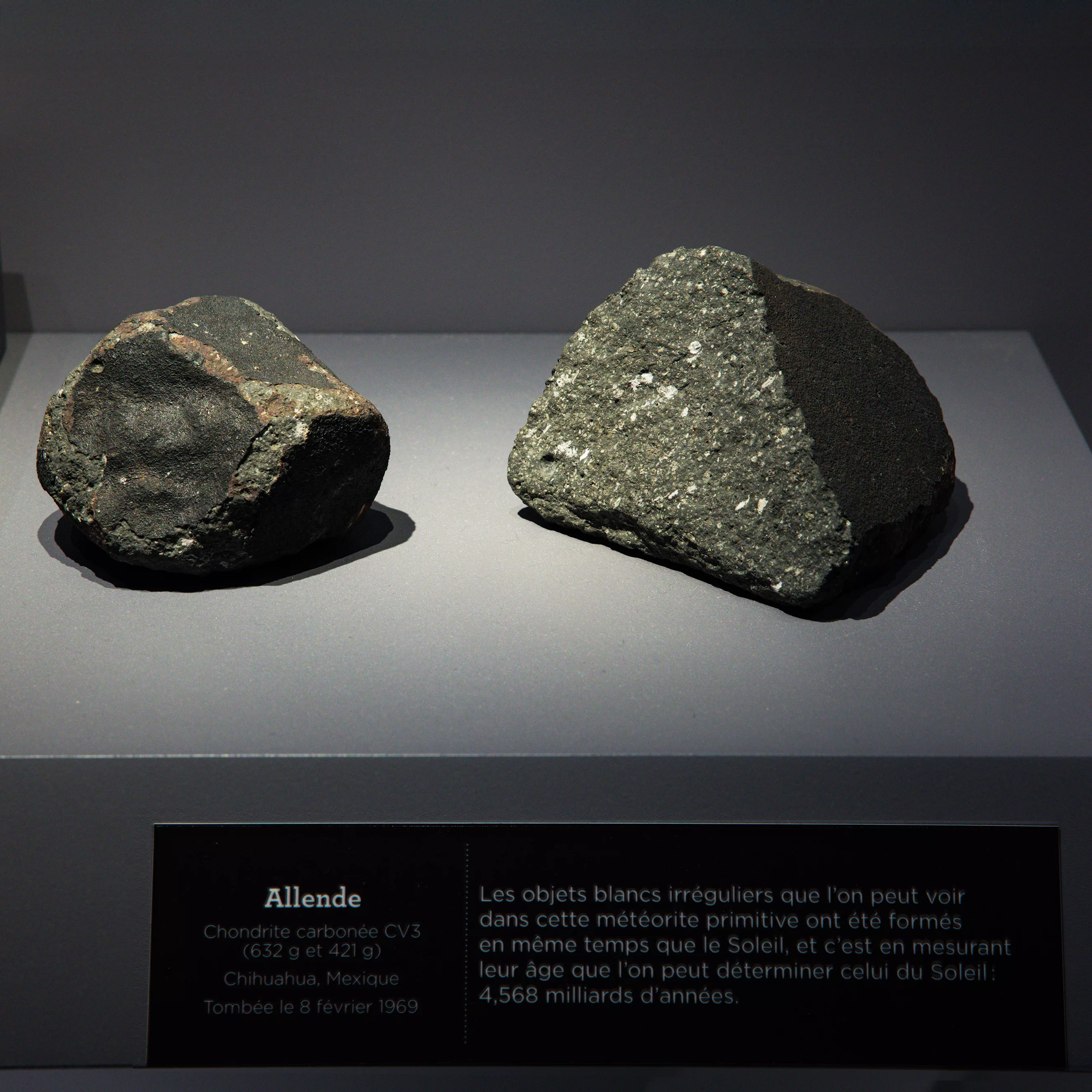

My doctoral research, however, had little to do with metamorphism. My thesis had focused on chondrites, especially H chondrites and presolar matter. At Fribourg, thesis topics weren’t assigned through a competition, but rather discussed during interviews with potential supervisors. Professor Marino Maggetti was looking for someone who could also care for the Institute’s collections: mineral specimens, some cut stones and gems, and a large number of old scientific instruments and crystallographic models. That’s when my passion for collections and for mineralogy really began to take root.

After Fribourg, I headed to Siena -a stunning city- for a postdoc. That postdoc gave me the opportunity of a lifetime: to join an expedition led by the national research council (Italy’s equivalent of the french CNRS) and head to Antarctica in search of meteorites.

You describe Antarctica as “the opportunity of a lifetime.” Could you tell us about that expedition and how it shaped the rest of your career?

Absolutely. I call it “the opportunity of a lifetime” because Antarctica is not a place you just visit, it’s not for tourism. At the time, you could only go as part of an official scientific mission. The conditions are extreme: temperatures range from -76 °F to just above freezing, and the weather can shift within minutes. Before departure, we underwent a field mountaineering training course: basic techniques, rope team progression, crevasse rescue… the absolute essentials to avoid any missteps once on site.

The journey itself began in Milan: Milan → Los Angeles, then Los Angeles → Auckland. That second leg was the worst flight of my life: we hit incredibly violent turbulence somewhere over the Pacific. I remember lying in the back of the plane, thinking I’d never see anyone again. But I made it to Auckland, then to Christchurch on New Zealand’s South Island, the main launch point for missions headed toward the Ross Sea. It’s easy to forget that Antarctica is larger than all of Europe. From Christchurch, we waited for a solid weather window before boarding a military aircraft. Once you cross the “point of no return” there’s no turning back. After a week of waiting, we flew seven hours and landed on sea ice.

“They warned us, “it’s slippery.” But after our training, we were confident… until we stepped out and landed flat on the ice. Everyone had a good laugh.”

From the Italian Baia Terra Nova base, we were flown by helicopter further south (between the 66th and 72nd parallels), about 300 km inland. We set up camp on a glacier in the Frontier Mountains and spent 59 days in the field, operating in total autonomy. Each day we covered a new section of the “white grid,” either by snowmobile or helicopter. On the ice, spotting a meteorite is relatively straightforward: it appears as a dark spot on a white background. When we found one, we stopped, followed strict protocols, and collected the specimen.

It’s worth noting that meteorites found in Antarctica rarely fell where they are recovered. Due to the flow of the ice cap from the pole toward the coast, they can be transported vast distances. When the ice hits a geological obstacle (mountain chain, for example), it rises, flows around it, and -thanks to the sun’s warming of exposed rock- melts slightly on the leeward side, revealing what was once entombed in the ice. These “blue-ice fields” are veritable meteorite traps. By the end of the expedition, we had collected 174 specimens, totaling 3.7 kg -mostly chondrites, no Martian meteorites this time, but a very nice collection nonetheless.

Back in Siena, I worked with several colleagues who specialized in transmission electron microscopy (TEM). What’s TEM for? It allows you to observe crystalline architecture down to the atomic scale, nowadays, even down to the ångström (10⁻¹⁰ m) level. You can even detect contrasts related to the electronic state of atoms within a mineral -for instance, whether it’s Fe³⁺ or Fe²⁺!

One day, an Australian researcher, Tim White, gave a lecture. He worked in Singapore and mentioned he was looking for someone with my expertise. At the time, I barely knew where Singapore was just “a potato-shaped island” on the map. He said, “Name your terms.” I was earning about €900 a month, so I tripled it, thinking I was being cheeky. He said yes immediately. And just like that, I moved to Nanyang Technological University.

In Singapore, I stayed in the orbit of crystallography and mineralogy but shifted toward synthetic materials: water decontamination systems, potential superconductors, and especially biomaterials designed to support bone regeneration after fractures. The human body isn’t just water and carbon, it has a skeleton, jaws, teeth: a whole mineral world. And much of that world is based on a family of phosphates known as apatites. That’s when my fascination with phosphates began. My chemistry colleagues would synthesize the materials, and I would examine their structures: what the synthesis yielded, how it was organized, and what it could be used for.

It’s important to understand that Singapore is a nation built on investment. Everything is geared toward monetization. Research is highly applied and innovation-focused. From a scientific point of view, it was incredibly stimulating: the resources seemed limitless. It was quite a contrast with the “old Europe,” as I would later realize upon returning.

What would you say to a curious young person who’s unsure about their future:how can we spark a passion for Earth sciences and materials science?

Since 2009, I’ve welcomed six to ten interns each year, usually middle school students in their final year; but this year, for the first time, I even had high school graders. To each of them, I say something simple: curiosity comes first. And curiosity, like friendship or love, needs to be nurtured. Nurturing it means being drawn to something and more importantly, wondering why that thing exists and what it’s for.

I’m talking here about the natural sciences. In science, nothing exists “just because.” In mineralogy, the first big question is: why do all these minerals exist? You won’t find the answer in four lines on Wikipedia. You have to love it, understand it, and accept that science means being a lifelong learner. Scientists “cost” society something: they don’t always produce things you can sell -patents are more the realm of engineers. And I don’t sugarcoat this for young people: doing science won’t make you rich. It’s not the most glamorous message, I’ll admit, but it’s important to be honest.

“You don’t go into this field to get rich; you do it because you want to answer questions. And to do that, you need support, from the government as well as private partners.”

My role with young people is to spark that curiosity, to sharpen it. At the start of a placement, students are often silent for the first two days. But then the questions start to come, and suddenly, there’s that spark: “Oh, so that’s how it works!” That moment is magic. That’s when the real conversation begins. Science isn’t about starting from an answer and looking for a question. It’s about starting with a problem and trying to solve it. History has shown us where the reverse can lead.

We also have to listen to young people. Many of them, often without realizing it, have a distorted view of science. In school, there’s sometimes too little theory. You make “ice from water,” but no one explains why. As a result, everything feels empirical. But if we correct that bias and give them the right tools, a whole new world opens up.

There are so many entry points. You can collect minerals simply because they’re beautiful, that’s perfectly valid. But learning the history and scientific reasons behind what’s glittering in a display case? That takes it further, it gives you something to share, to pass on. There are also study paths to follow: geology, geochemistry, materials engineering… there’s no shortage of options.

One last, and very timely, point: screens. Gen Z absorbs information through their phones, often without any filters. They need to learn how to filter, how to ask questions. If we can teach them that, then we’ve got real potential for future scientists -whether they become mineralogists, chemists, physicists, mathematicians, or engineers.

One last anecdote: last year in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, I ran into a former intern who had come to the museum four years earlier as a middle school student. I hope his passion stays with him. With a bit of luck, maybe before I retire, I’ll see him working here at the museum. That would be a truly fulfilling moment.

“If there is no minerals, there is no life”: from smartphones to society, how do minerals shape our daily lives and why do collections matter?

I’ve said it before, and I deeply believe it: without minerals, there is no life, let alone a modern world. Whether in solid or dissolved form (especially in water), minerals form the foundation of everything around us.

Why should minerals -with a capital M- be better known? And why are mineral collections like the one at the Paris NMNH so important? Because in our everyday lives, almost every single action we take involves minerals in some way.

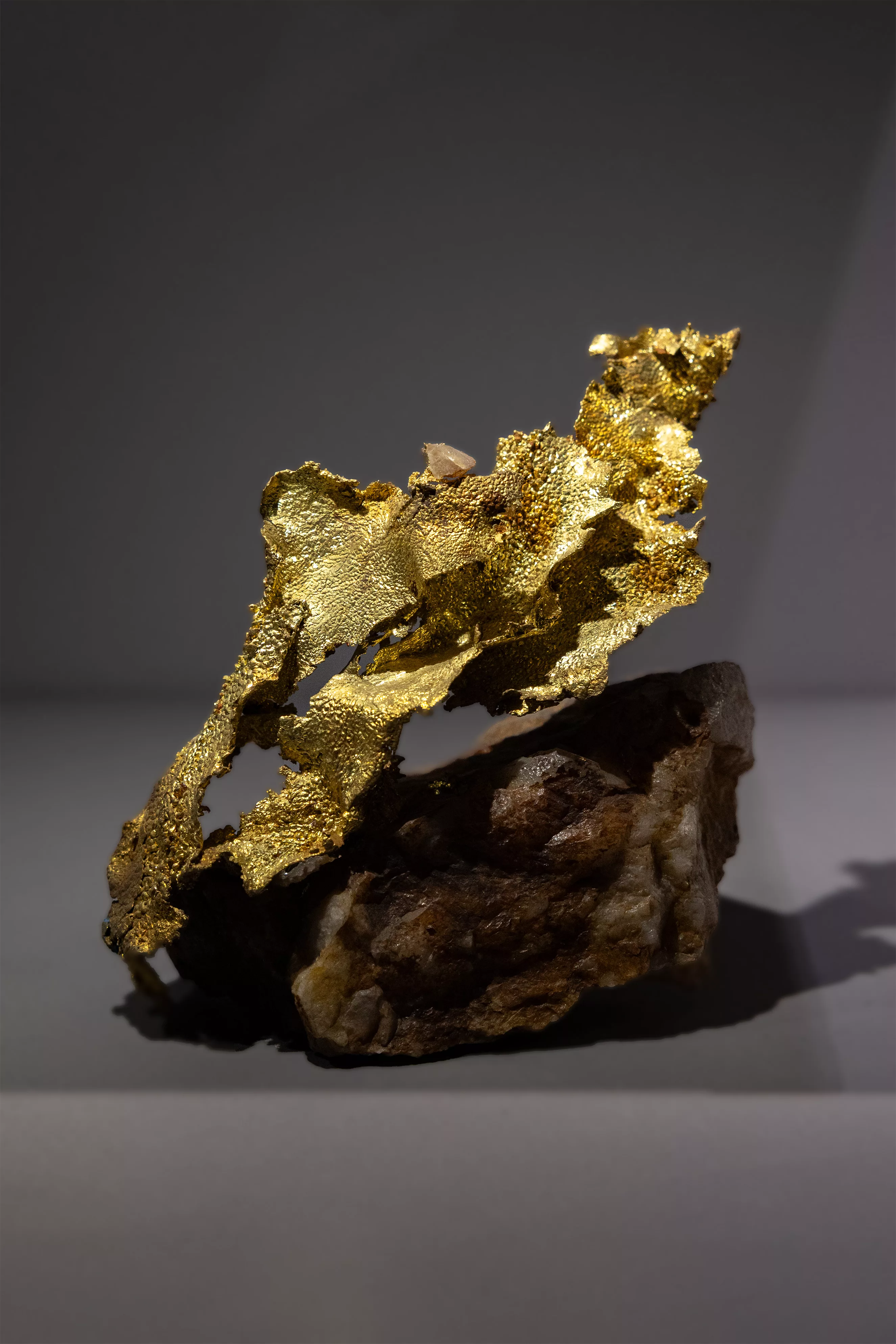

A smartphone is like a pocket-sized collection: gold, copper, silicon, rare earth elements… over twenty different chemical elements gathered in the palm of your hand, all extracted from the Earth. The same goes for microchips, integrated circuits, superconductors, batteries, electric cars, household appliances, and even the lenses in your glasses. Strip away the plastic -which itself comes from a mineral resource, hydrocarbons- and what remains is mineral. Even the plant world thrives because roots draw nutrients… from minerals. Without them, nothing holds together.

Mineral resources also shape history and geopolitics. A significant share of today’s global tensions can be traced back to resource access: in Africa, around “coltan” (columbite and tantalite); in Asia, where rare earth elements (of which China is a major exporter) power global technology. We can talk about all kinds of justifications, but at the core, it’s nearly always about raw materials.

This is exactly why public collections matter. Our drawers aren’t forgotten attics, they’re memory banks. I like the image of a binary system: an empty drawer is a zero; a full one is a one. Display cases offer beauty, but science also relies on what isn’t “spectacular.” Each specimen carries knowledge built by generations of researchers, and many are now irreplaceable: the outcrop is gone, the hill leveled, a road runs through the old site. Preserving, documenting, making available, this is essential for understanding, and ultimately, for using resources wisely. Ethics can be debated, but the practical reality is beyond question.

Across Europe, we’re now seeing the cost of our dependence. There’s renewed talk of geochemical prospecting, reopening quarries and mines, because importing raw materials has become too expensive. Prospecting, extracting, processing, making usable -the entire chain needs to exist. And yet, from the early 1980s until very recently, this chain unraveled in France; mineralogy as a discipline was nearly wiped out. But the collections held firm. They provide reference points. They give us something solid to rebuild from.

That’s why the Galerie de Minéralogie plays such a vital role: it connects the most ordinary gesture (a call, a photo, a commute) to its mineral foundations. It reminds us where our know-how comes from and why we must protect it. No minerals, no technology. No memory, no future.

How was the mineralogy collection at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle created and enriched over time?

If I had to choose a starting point, I would say July 8, 1626. Under Louis XIII, the Royal Garden of Medicinal Plants and its “Droguier du Roi” were established here. At the time, a droguier brought together both organic and inorganic substances -plants and minerals- for use in pharmacology. Some minerals were believed to have healing or therapeutic properties, and that early nucleus became the foundation of our current collections.

The Droguier du Roi survived the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV (who died in 1715). Upon the latter’s death, his successor sought to “lighten” Versailles, and some collections, such as ornamental stoneware and vases, were transferred here, to what would become the Jardin des Plantes. In 1729, it officially became the Royal Garden of Plants in Paris, ushering in a golden age that culminated under Buffon, the Garden’s intendant. Buffon brought structure and vision to the collections, and through his diplomatic network, the Muséum received prestigious gifts: specimens from Christian VII of Denmark, the Tsarina of Russia, the King of Poland… This was also the era of the great Florentine Table and the two others known as La Perle and La Pomme-grenade, created at the Gobelins Manufactory.

It was a moment when art and science reemerged, and alchemy gradually gave way to an emerging field of chemistry. I like to quote what Guy-Crescent Fagon, chief physician to King Louis XIV, wrote around 1689 in a handwritten note: “Quartz morion may not be all that useful against rheumatism, but once cut, it becomes a work of art.” Today that sounds amusing, but back then it marked a shift from medicinal use to aesthetic appreciation. In the same spirit, people once chewed kaolin to whiten their teeth -polishing them to the point of damage-

“and believed mercury prolonged life…”

The year 1793 was pivotal: it marked the official founding of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. Each scientific domain was given its own professorship: botany, mineralogy, geology, ornithology, and so on. On the mineralogy side, the chair was held by a distinguished line of scholars: Daubenton, Dolomieu, Haüy, and later A. Lacroix (1893–1937), J. Orcel, J. Fabriès, and M. Guiraud until the laboratories were disbanded, but the momentum had been set.

From 1626 to today, the collection has grown along two major paths. First, through royal and state collections: after the early pharmacopoeia phase, more decorative and scientific objects soon followed. Second, and this is essential, through donations. Learned collectors and visionary scientists entrusted their collections to the Muséum: in the early 19th century, the Weiss collection (at the time one of the finest in the world); later, Gillet de Laumont with over 2,500 specimens; and many others, both prominent and lesser known. In more recent times, Colonel Louis Vésignié stands out: part of his collection went to the Muséum, the Sorbonne, and the École des Mines; the Muséum later acquired the rest. Today, we preserve over 20,000 specimens from his legacy.

Why are these donations so important? Because in today’s context (tight public budgets and shifting priorities) our purchasing capacity is minimal. Donations allow us to enrich both public exhibitions and research collections (those “drawers” which, like the brain, only serve their purpose when full). They also preserve samples from sites that no longer exist, making them an irreplaceable material memory.

In France, the tax framework for philanthropy is favorable: donors can deduct monetary gifts from taxes and even target specific areas (“I wish to support this collection, or this acquisition”). Progress is slow, but it is happening. Elsewhere, the dynamic is much stronger: in the Gulf States, new museums open every year. Of course, they have financial means, but more importantly, they have a clear understanding of why it matters: to pass on their history and scientific foundations to future generations. France can and should accelerate.

One final, essential point: the Muséum is a national institution. Everything that enters here belongs to the French people. Our role is to safeguard the past, serve the present, and pass knowledge to the future. Donations are not only acts of generosity, they are acts of cultural sovereignty.

In the Gulf States, the U.S., and China, the development of natural history museums is often supported by the mining and energy sectors. The MNHN itself once benefited from a major sponsorship by Elf–Total. What did that partnership make possible, and what would a “virtuous” form of corporate sponsorship look like today and beyond?

This is a complex issue, shaped by different eras and generations, each with their own outlook. The Elf–Total sponsorship began in 1983, in the wake of the oil crisis of the 1970s. At that time, oil companies had the financial means and a cultural approach very different from today. Thanks to the foresight and diplomacy of my predecessors, that partnership took root and lasted until 2011. The result: approximately 1,700 major specimens were added to our collection.

After 2011, the landscape shifted: accidents, environmental disasters, growing social pressure… Energy companies began redirecting their support toward more environmentally conscious initiatives.

Will we see the immediate return of a single, major sponsor? I don’t believe so, not right away. But change is happening so fast that we must remain open: a 15-year-old today may, in ten years, be working in a profession that doesn’t even exist yet.

Why do I think these industries will, sooner or later, reengage with institutions like ours? For a very simple reason: we hold the memory. We preserve the record of former mines, quarries, reference lithotheques. The samples that document past extraction sites are here. And to envision new types of deposits, understand supply chains, and secure strategic raw materials, this knowledge base is indispensable.

Let me make a personal aside here: I don’t believe in electric energy as it’s currently conceived. Generating electricity, storing it, managing end-of-life batteries that are often poorly recycled… this can be more polluting than some fossil fuel sectors, unless we radically rethink production methods and usage. This is an entirely personal opinion, but it explains why I believe industry will need robust mineralogical knowledge -knowledge preserved in public collections.

In practical terms, I expect future sponsorships to be more targeted: “small” by the standards of a major corporation, but decisive for us and driven by a broader sense of responsibility. And let’s be clear: meaningful sponsorship doesn’t only fund acquisitions. It supports conservation (equipment, storage, environmental controls), documentation (photography, databases), digitization, public outreach and, above all, people: short-term contracts, technicians, collection managers. Putting everything online? Great! But it requires time and skilled hands.

In summary, the Elf–Total legacy enabled us to acquire an exceptional number of major specimens. The path forward will likely involve multiple partnerships built around a simple, threefold mission: acquire when relevant, preserve and study, and share with the public. That’s how a national collection remains dynamic and useful to society.

If you had a magic wand, what would your ideal exhibition look like?

If I had a magic wand, I’d design an exhibition in three parts: beauty, utility, and responsibility.

First, beauty: telling the story of four centuries of collections through the wonders our Earth has to offer. Showcasing these aesthetically striking specimens means honoring our sense of wonder, where our gaze, our taste, our cultural history all come from.

Next comes the “utility”: showing that the minerals displayed in the cases are the very same ones, sometimes smaller, sometimes even invisible, that keep the modern world running. The aim is to help visitors sense that what they handle in daily life and what they admire in the museum are bound by a direct thread: without one, the other could not exist.

The third part would be about responsibility: retracing how extraction practices have evolved. From the Neolithic to Antiquity, humans made what we would now call ecological disasters. Think of the widespread deforestation driven by the need for charcoal to smelt iron. Up until the 8th century CE, much of Europe was almost completely deforested; the last few remaining primary forests are still found today in parts of Poland.

Today, we’re learning from those mistakes. A quarry is still a scar on the landscape but modern management includes site rehabilitation, water treatment, and reintroduction into the ecosystem. First law of physics: every action has a reaction. We can’t escape that, but we can act with awareness.

I’d like to end this journey with a look at our own habits, our consumption. Why four phones when one is enough? Three cars? Every choice comes with a consequence. After walking through this exhibition, I’d want visitors to walk out understanding this: there is beauty, there is necessity, and necessity comes at a cost. What can we each do, at our own level, to reduce that cost?

“I don’t live in a fantasy world: without political will, there’s no magic wand.”

But I’m already grateful that a small, modest part of the Gallery of Mineralogy and Geology has returned to its original purpose: to showcase minerals. Originally, this space covered a much broader spectrum; it once embraced all the Earth sciences. From 1841 to 1898, paleontology was part of this gallery before being moved to its own building at the far end of the Jardin des Plantes. This place should become a living, breathing center of knowledge again, not just a beautiful but frozen hall.

Because our collections are very much alive: every year, we send 150 to 200 samples to scientists around the world. Since I started here, eight new mineral species have been described from specimens in our collection. Dozens of scientific articles have been based on the samples we preserve. After entomology and botany, mineralogy is the third most prolific discipline in terms of new species: 10 to 15 per month, on average. In nine out of ten cases, these species are discovered in museum collections, sometimes even in meteorites.

That’s why this heritage is not a thing of the past trapped under glass: it is a laboratory for the present and the future.

What role does volunteering play at the Museum today?

Fortunately, we have volunteers. Here in the Mineralogy department, we have 14 of them. Without their help, an institution as “prehistoric” as the Museum would face serious daily challenges.

That said, the reality isn’t simple. Around 95% of our volunteers are retirees. There’s little generational renewal, even though a few younger people do join us. Too often, their work goes unrecognized, which can be disheartening and lead some to stop volunteering altogether.

Thankfully, the human bonds are strong. But to sum it up: volunteer work is essential and part of the Museum’s day-to-day life, here and across the institution. It deserves greater recognition and more material support, if only to attract and retain the next generation.

Is there someone you’d love to see interviewed as part of this series? And if so, what question would you ask them?

Any major political leader.

I would ask them, in truth, a single question broken down into several “whys”:

Why must it take a disaster for us to wake up?

Why does a building have to collapse before we finally decide to restore it?

Why do we have to lose something to realize its importance?

And above all: why does Culture -with a capital C- no longer have a central place in our society?

In the current French context, should we rely more on public institutions or on civil society to move culture forward?

All great civilizations, and what they leave behind, are built on culture, meaning knowledge. Yet today, I see that certain public and media dynamics no longer encourage long-term thinking, nuance, reflection, or transmission. The flood of uneven information, combined with a decline in academic standards and the value placed on effort, creates a sort of noise that ultimately weakens general knowledge and our ability to think freely.

In Paris -the so-called “City of Light”- this is something you can feel daily: public discourse is growing shallower, and the intellectual effort required for deeper understanding is fading at an alarming rate.

Ideally, if the political class finally grasped the magnitude of this issue and genuinely wanted to solve it, it would still take one or two generations to rebuild the foundation, meaning the education system. It all starts with education: that’s where instruction begins, and where culture becomes accessible. With instruction and culture, the number of valuable ideas increases, and by the law of large numbers, the likelihood that some will emerge and be successfully implemented increases as well. That’s the foundation.

Without it, I don’t see how any real, lasting solution can take shape. And in the long run, it’s hard to imagine a healthy balance between highly funded cultural “niches” and less privileged sectors. There are nearly 9 billion of us on this planet;

“the real challenge is to turn 9 billion people into 9 billion thinking minds. Investing in that is essential.”

That’s why, personally, I lean first and foremost toward public institutions, places of memory and transmission. If we succeed in strengthening those, future costs will drop, wealth creation will be more diverse, and the results more tangible.

I don’t have any illusions. One has to deal with reality with its slow processes and endless meetings where the only decision made is to set another meeting. But despite the frustration, I continue to pour all my energy into keeping the collection alive, ensuring the science it supports advances, and making those results accessible to as many people as possible. To achieve this, we need resources -public, private, donations, sponsorship, volunteer support- and I will keep seeking them in every form we’ve discussed.

Concretely, how can we rekindle young people’s interest in minerals?

In my view, there are two very tangible levers to spark -or rekindle- young people’s interest in minerals: ensuring material access, and then igniting curiosity.

First, access. Through Terre Minérale, you’re already doing a great deal by opening up the conversation and that’s crucial, because this world we often imagine to be “elitist, niche, closed-off” really isn’t. The real obstacle is often much more down-to-earth: cost.

Take a young person from Paris who wants to attend the Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines show: train, accommodation, meals… and, if possible, a bit of spending money to leave with a few specimens. Three days, and you’re close to €1,000. How many can afford that? Almost none. The most “straightforward” solution, if I may say so, is to make the local scene thrive. Reducing logistical costs means making it possible for young people to buy a specimen at a fair price.

“A small object can spark a big passion.”

And as you well know, when a young person becomes passionate, it spreads quickly within their group: “Look what they found… I want one too!”

From there, another obvious extension is the digital realm, which ties into the second lever: cultivating curiosity where it doesn’t yet exist. Social media is powerful:the brain–screen interaction is real. Let’s provide simple, regular formats: short talks, “Mineralogy for Beginners,” bite-sized educational videos. It’s all feasible. We should also knock on every door we can: propose one-hour weekly sessions in middle and high schools, create recurring events. Word of mouth will do the rest. Without stimulation, nothing happens. But the moment a piece of content speaks to someone, the ripple effect can be explosive: within days, dozens, then hundreds, then thousands of views. That’s the spirit of your initiative, I think: to open access to as many people as possible using the tools of today.

Here, civil society has a vital role to play. Large institutions or corporations aren’t meant to do everything; things come to life through local networks: a club, a school, a parent volunteer, a collector who gives an hour to explain a crystal to a child. That’s how we build tomorrow’s culture.

There are already some great participatory programs here at the Museum. One example is the Herbarium through “Recolnat,” where the public helps classify and organize collections via a web platform. It works because there is a large enough team to dedicate staff to oversight. In Mineralogy, we’re a small team, we can’t do everything. But if you asked me, “Would you take part?” the answer would, of course, be yes.