Article published June 25, 2025.

Interview: HBM – Photo credits: © A. Certain / Musée de Minéralogie Mines Paris – PSL

A hidden gem even for many Parisians, the Mineralogy Museum at the Paris School of Mines is one of those century-old institutions that have shaped modern France. At a time when the dream of a seamless globalization is increasingly seen as a utopia, a museum designed by and for engineers and not just as an exhibition space, is an essential asset for the innovation and the development of future technological breakthroughs. Explore this historic, forward-looking place with Éloïse Gaillou.

To start, could you briefly introduce yourself to our readers?

I am Éloïse Gaillou, director and curator of the Mineralogy Museum at the Paris School of Mines (Mines Paris – PSL). I joined the School in 2015 and have been running the museum since 2024.

What interests me most is nature and everything that’s connected to it.

I come from a small village, in the West of France. There wasn’t much to do there… except to go for walks and observe what was all around me… including under my feet. And under my feet were fossils. That’s how my first passion began. I grew up on Jurassic terrains, remnants of an ancient sea. I used to search for marine fossils that came from the deep. That’s what gradually led me to rocks.

My parents also often took me to the mountains. In the Alps, before I was 10, I discovered the fascinating world of crystal hunters. There were these little shops along the trails… I think that’s when my curiosity for minerals really started to take shape.

Then came my first “collection”, thanks to National Geographic. Every month, I’d receive a little box containing a mineral, accompanied by a descriptive sheet with its name and main characteristics. It was simple, but fascinating.

At the time, I had no idea you could actually study this field. What fascinated me were the sciences in the broadest sense: math, earth and life sciences. I just loved it.

Your academic background brought you to where you are today. Could you tell us more about it?

At first, I was more interested in animal-related studies. But when I visited the science faculty at the University of Nantes, I discovered the geology department. I had no idea that there were people whose job was to study rocks! Out of curiosity, I went to the open doors, where the geologists welcomed us with open arms, happy to share their passion. At a large university like Nantes, few students choose that path. They showed us the labs, their research, their experiments… it was fascinating. That’s when I knew this was the direction I wanted to take.

Initially, I thought I’d only study for a year or two. But once I got to university, I discovered a wide range of courses: classical geology, mineralogy, metamorphic geology… and then gemology, the study of gemstones. I was immediately drawn to mineralogy and gemology. So, I naturally chose to specialize in this field. The desire to go further just kept growing. After getting my “Licence” degree, a Master’s felt like the logical next step. I loved both the research topics and the fieldwork: it had a hands-on aspect and a desire to better understand geological materials that were still not well-known.

When my chosen specialization, petrology, was no longer offered in Nantes, I continued my studies with a second-year Master’s in Clermont-Ferrand at the Laboratory of Magmas and Volcanoes. There, I specialized in petrology, with a focus on magmatology and geochemistry. Up to that point, my research had been mostly centered on metamorphism, with a touch of geochemistry. My research was about sapphires from France’s Massif Central, and specifically those forming in a magmatic context: a good way to maintain that link between geology and gemology.

After that, I received a regional grant to pursue a PhD at the University of Nantes, studying opals, their formation and internal structure. After eight years of academic training, I finished with a doctorate in hand, along with a University Diploma in Gemology (DUG). At the end of my academic career, I started applying for jobs, particularly postdoctoral positions. Soon, colleagues advised me to try my hand abroad, especially to the United States, which is almost a rite of passage in the research world. It’s a great way to improve your English, but more importantly, to discover new ways of working and different scientific approaches.

Thanks to presentations I’d given at international conferences, I had built a network. At the time, geologists specializing in gemology and non-destructive analysis techniques were still rare! One of those contacts led to a specific person and institution: Jeff Post from the Smithsonian Institution. We discussed an exciting research project on colored diamonds -specifically the extremely rare pink and blue ones. It was a relatively unexplored subject, because very few universities had access to such rare (and expensive!) samples, and most museums didn’t necessarily have the expertise or equipment to study them properly.

So I headed to the United States to the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution, to start studying these colored diamonds, mainly the blue and pink ones, from the museum’s world-famous collections. I was supposed to stay for a year. In the end, one year turned into two, and then a new research project emerged. There was still so much to explore. I started by working on pink diamonds, then shifted my focus to blue diamonds.

I really enjoyed being there. That’s where I truly discovered the museum world, which I didn’t know at all. Up to that point, my career had been entirely academic. Everything related to collections -how they are managed, displayed, and shared with the public – was completely new to me.

That’s when I realized: “This is what I want to do.” What appealed to me was this unique combination: the collection, the research, the outreach, the exhibitions… and also the relationships with collectors and other curators. That balance between scientific rigor and public engagement won me over completely.

But a postdoc, by definition, remains a fixed-term contract. Eventually, I had to find a “real” position. So I began applying for jobs back in France, especially early-career researcher positions. But my applications were unsuccessful. At the time, my work combined geology and gemology, using techniques that weren’t yet widespread in academic geology.

But what was not appreciated in France was in the US! I first time applying for a job in the US was in 2011, for a position of associate curator at a museum. When I presented my research, my profile generated genuine interest.

“I had real museum experience, I worked on gems and minerals, and I used non-destructive analytical methods, which matched perfectly with the expectations of a museum institution.”

The job at the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History was very exciting, and my colleagues were fabulous – I learned a lot from them (though I have to admit, I didn’t enjoy the city itself very much!). The museum made a big impression on me, particularly in terms of its approach, which was very different from that of the Smithsonian’s.

At the Smithsonian, everything was highly structured. Each department had a specific role: exhibits were handled by dedicated teams with no direct connection to the curators. The education department managed the children’s programs. Then there were the scientific teams and those in charge of collections. Everyone had their own clearly defined space and role, and interaction was limited. In Los Angeles, things were more flexible. The museum was smaller, and curators in mineralogy had control over almost everything: access to the collections, the specimens, scientific instruments, as well as the scenography. If a specimen wasn’t quite right, we could replace it. We wrote our own mediation texts and designed the temporary exhibitions.

It was all very exciting. And that’s when I knew for sure: this is what I wanted to do.

At the end of 2024, my French colleagues told me about an assistant curator position opening up in France at the Paris School of Mines. They also mentioned that the current head curator and museum director would be retiring soon, so there was a potential for advancement after some time on the job.

This position matched my expectations in every way. It gave me direct access to an extraordinary collection: historic, prestigious and internationally renowned. It also offered the opportunity to contribute to the permanent exhibition, to design temporary exhibitions and take part in all the key responsibilities of a museum. And I still hoped to continue doing a bit of research on the side.

That’s how I ended up here. In 2015, I began as assistant curator. Then, gradually, I took on the role of curator. And when the director retired, a formal hiring process was launched. I applied and in 2024, I was appointed in January 2025.

“The role of a museum is to research, collect, conserve, interpret and exhibits tangible and intangible heritage.”

The Paris School of Mines is one of the earliest “grandes écoles” founded to train civil engineers and the elite of the French state. How do you explain the fact that it houses one of the finest mineral collections in the world?

It’s important to know that, originally, mineral collections weren’t unique to the École des Mines. Almost all scientific universities and “Grandes Ecoles” had their own collections, primarily for teaching purposes.

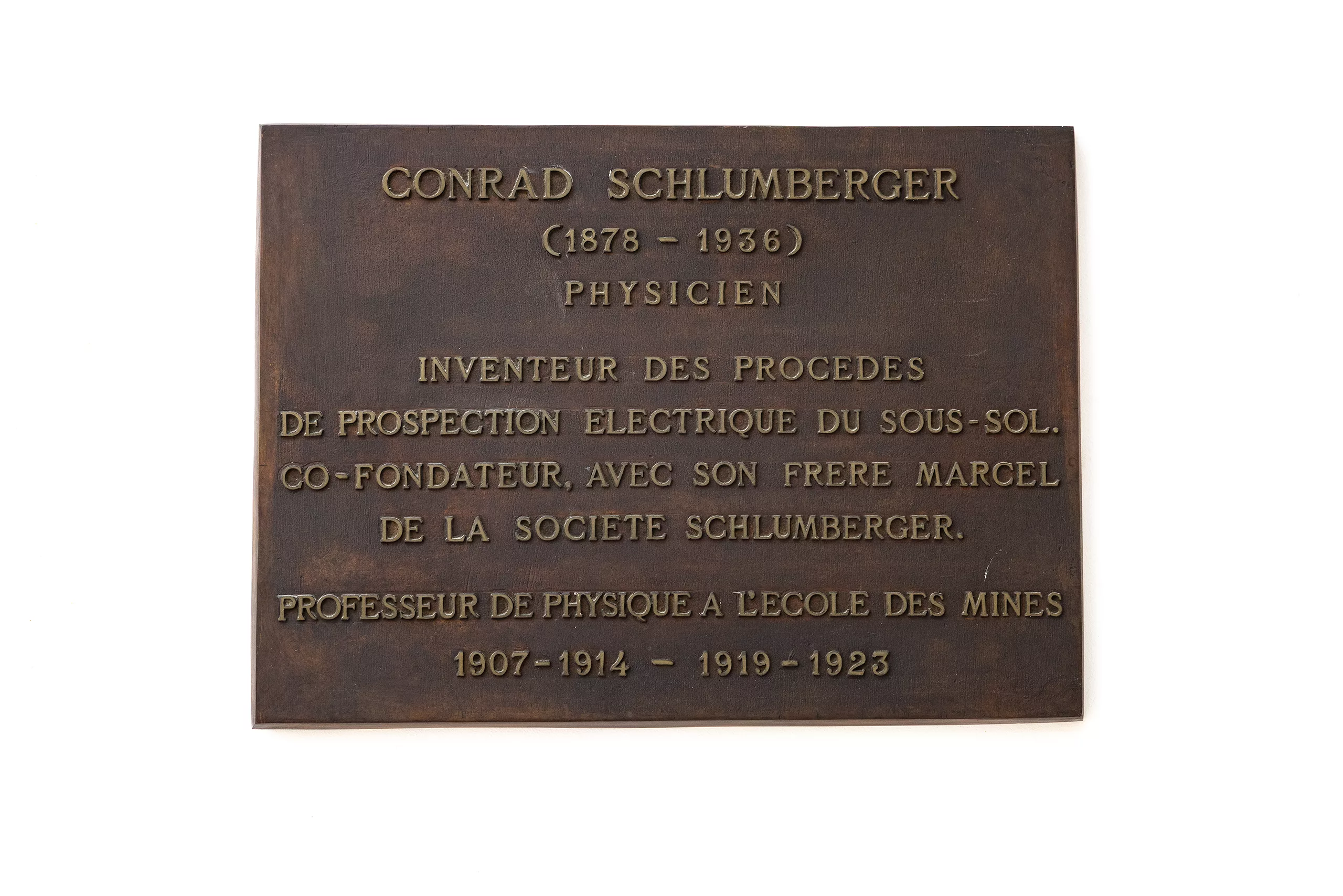

But l’École des Mines de Paris holds a somewhat special place. Founded in 1783, its mission was to train mining engineers capable of identifying and extracting underground natural resources. The school’s very first director, Balthazar-George Sage, was chosen by King Louis XVI because he already had his own collection of mineral samples and taught mineralogy.

During the French Revolution, there were major institutional changes, a new director was appointed, and an official collection created. The Comité de Salut Public decreed the creation of a comprehensive mineral collection designed to catalog the Earth’s potential resources in a systematic way: organized by geographic locality, not only in France but across the world. Each specimen had to be classified by its place of origin, in a meticulous and organized manner. That’s how what was then called the Cabinet des Mines (Mines Cabinet) was born. It had a threefold mission: to conserve, preserve, and display. Its first curator in 1794 was none other than Abbé René-Just Haüy.

From the outset, the Cabinet – today’s Museum of Mineralogy – had a public mission. It was open to the public two afternoons a week, offering people the opportunity to discover the wonders of the natural world. In a way, it had a museum-like role long before the concept was widely established.

That mission still continues today. To conserve, protect, study, explain, and exhibit: that’s what defines a museum. Unlike a gallery, a museum maintains a permanent, documented, studied, and shared collection. That’s why we want to make it clear: we are a museum, with a permanent collection, a permanent exhibition, and a history that goes back to the end of the 18th century.

Even though the Paris School of Mines no longer trains mining engineers, the collection itself has lost none of its value. Designed from the very beginning as a reasoned, systematic inventory of nature, it deserves to be preserved, passed down, and shared with the widest possible audience.

Its official name reflects that heritage: Collection of the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris (ENSMP).

What major differences do you see between the museum approach in France and in the United States?

There are several factors to consider when comparing museum approaches between France and the United States. Of course, there are differences between countries, but the nature of the institutions themselves also plays a key role.

The Smithsonian Institution in Washington and the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles are both major institutions with outstanding collections. Yet even within the same country, practices can vary greatly depending on how departments are organized internally. At the Los Angeles museum, for example, in the mineralogy department, we still had control over the exhibitions -which wasn’t necessarily the case elsewhere in the museum. In other words, the level of autonomy a department has often depends less on the country than on the structure of each institution.

A striking point is the relationship between curators, collectors and dealers, which is very different from what we see in France. In the United States, these ties are natural, and curators are much closer to the market. Even the curators of smaller museums attend mineral fairs.

And it’s not just curators. You’ll also find scientists, researchers, and geologists at these shows. Some go for pleasure, others to buy specimens useful for their research, or to build a small personal collection. This exchange between the academic world and the market is natural.

In France, that kind of interaction between academia and the market is much rarer. I’ve often had to suggest to researchers that they attend a mineral show to buy a specimen for a few euros, rather than requesting a loan of a heritage sample that we can’t give away. This lack of familiarity reflects a more general compartmentalization between research, collections and the market, both cultural and institutional.

This separation also affects sponsorship and patronage. In the United States of America, the direct relationship between museums and collectors encourages donations and financial support. Philanthropy is not only more common but also more celebrated. Tax incentives are stronger too (up to 100%), compared with 60 to 66% in France depending on the situation.

But beyond taxation, it’s above all a question of visibility. In the United States of America, donors like their name to be associated with a showcase, a room or an object. It’s a way to have a visible presence in the cultural and scientific space, a public statement of support. In France, it’s usually the opposite. Collectors prefer to keep a low profile, not to display their objects or put their names on them. Donations or loans remain confidential, almost anonymous. This reserve also extends to relations between collectors and curators, who rarely move in the same circles.

Across the Atlantic, curators are more visible: present in the media, in direct contact with the public, and very much the face of their museum. This openness is also reflected in how private collections are promoted. At major shows like Tucson, collectors and museums set up their own showcases, take part in competitions and are proud to be recognized. There are even prizes for the best displays.

In France, initiatives like that are still very rare. Few, if any, private collectors exhibit their pieces publicly in a competitive setting. In the U.S., that kind of public recognition is fully embraced. It’s one of the defining strengths of the TGMS, the main show in Tucson: those showcases, designed by collectors and curators for the general public, are the heart of the event. They’re meant to be seen, admired… and celebrated.

You mentioned cultural differences around philanthropy. Concretely, what role does this kind of support play for your institution?

If we go back to the origins of the collection, in 1794, the goal was very clear: to create an inventory of natural resources, both in France and around the world. The challenge was that they were starting from scratch. So, the first step was to acquire preexisting collections, such as those belonging to scientists, teachers and professors, to lay the foundation.

Meanwhile, teachers from the École des Mines were sent on field missions to collect samples directly. But most importantly, we must remember that the School was training mining engineers, who went on to work all over the world. At that time, enrolling at the School came with a kind of return obligation: once they graduated, engineers were expected to contribute to the life of the institution, notably by enriching its collections. That might involve donating specimens from the mines where they worked, or facilitating connections that allowed the School to acquire samples directly from producers.

This strong bond between alumni and their school helped the collection grow rapidly. After the initial purchases, the bulk of the collection expanded thanks to what could be described as scientific and material patronage, driven by a deep sense of loyalty to the education they had received.

Over time, that dynamic opened up. Once limited to alumni, this form of contribution is now open to everyone. Anyone can help enrich the museum, whether by donating minerals or providing financial support. It’s a way for those who haven’t studied at the School to leave their mark and becoming part of its story.

But things have changed. Today, mining operations in France are virtually nonexistent. And the Paris School of Mines hasn’t trained mining engineers for several decades now. That role is more associated today with the École des Mines de Nancy, which has maintained a focus on mining engineering.

At the Paris School, students now train as generalist engineers, specializing in fields like management, industrial strategy, or energy transition. Their connection to direct mining operations has faded. They no longer design or run mines. Instead, their work increasingly involves analyzing the environmental, geopolitical, and industrial implications of resource extraction and use. Their role is now more downstream: in resource transformation, supply chain management, and impact assessment.

This shift from fieldwork to global analysis reflects the very evolution of the School: from mining to industry, from extraction to understanding of today’s challenges.

In what ways are today’s major global challenges reflected in your current projects?

Paris School of Mines still holds a unique position today: it’s one of the few places where the connection between raw materials and final industrial applications is so clearly established. Whether it’s large corporations, start-ups, or players in emerging technologies, the School remains at the heart of the issues surrounding the transformation of natural resources.

This role is reflected in the “savoir-faire” (craftmanship) the School is working to revive. I’m thinking, for example, of a recent exhibition we devoted to synthetic crystals. These crystals, indispensable in cutting-edge technologies such as lasers, telephony and aeronautics, used to be produced in France. Over time, however, their manufacture has gradually been relocated, notably to Russia. Today, the challenge is clear: to relocate production and redevelop skills in France.

The museum is fully committed to this dynamic. The purpose of the exhibition was precisely to show how this expertise is being reborn, thanks to scientific progress, but also to the companies that came and presented their processes here at the museum. For us, it’s natural and even essential to give a voice to these industrial players. After all, it’s all about extracting, transforming and mastering materials. Take ruby crystals used in red lasers, for example. Their performance depends on the very precise concentration of chromium. Achieving the right properties requires meticulous control of impurities. These kinds of subtleties are what we wanted to make visible and understandable to students, professionals, and the general public alike.

Another example is our collaboration with the Orange Foundation on recycling mobile phones. The exhibition showcased the minerals needed to manufacture phones, with the actual components taken apart. What was striking was their extreme miniaturization, and consequently their very low recyclability. The more complex and small the objects, the harder they are to reuse. This is exactly the kind of issue our students are working on. The museum acts as a link here: between the research conducted at the School, industrial realities, and public concerns. It becomes a place where knowledge, craftmanship, and social issues intersect.

But for all this to work, we need resources. And this is where philanthropy is absolutely vital. While the museum is part of the École des Mines, the School is, first and foremost, a higher education and research institution. The museum is not a budgetary priority.

What’s more, we don’t report to the Ministry of Culture or Higher Education, but to the Ministry of the Economy and Finance. This excludes us from answering to proposals supporting cultural or university projects!

“To put it plainly: we have no public funding for temporary exhibitions or acquisitions.”

Everything we do, such as enriching the collection, new exhibitions and educational programs, relies entirely on sponsorship. This is what enables us to innovate, educate and bring this unique collection to life, by connecting it to contemporary issues.

We understand from your words that minerals shape our lives without us necessarily realizing it. What distinguishes a material that’s mined for its properties from a specimen preserved for its scientific or heritage value?

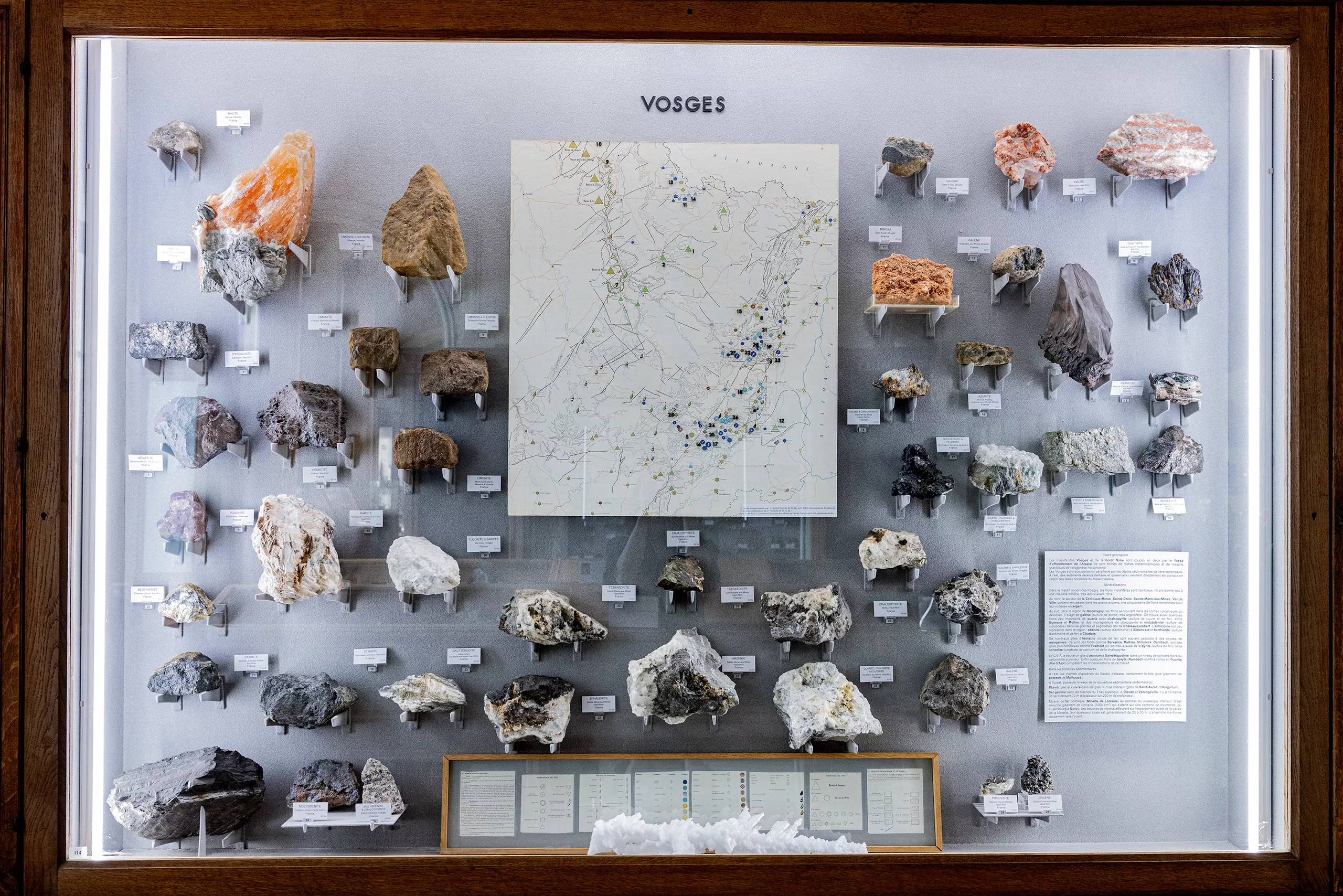

At our museum, we preserve both. Part of the collection serves as a true inventory of natural resources by deposit. It includes ores, in other words, raw rocks that may seem unimpressive to the naked eye but contain valuable elements. This segment still represents about 15% of our entire collection, as well as of the current exhibition. We present it using maps, particularly maps of France, that show the location of major deposits: silver, gold, copper, tungsten, rare earths, uranium… These are the materials that feed industry.

In the rest of the exhibition, the museum highlights the aesthetic beauty of minerals through a systematic display, with more than 1,200 mineral species shown to the public. These are exceptional pieces, yet paradoxically, they’re not the ones mined for industrial use. In mines, the minerals that are truly exploited are often microscopic, embedded within rock, present in the form of ore. What matters there isn’t their appearance, but their chemical composition.

The museum itself has evolved in that direction. In the past, industrial ores were more commonly displayed. Today, we’ve made a different choice: to spotlight the natural wonders. Not to hide the rest, but because beauty draws attention. And it’s that moment of wonder that opens the door to education. Behind every magnificent specimen is a story of raw materials, industrial applications, and contemporary challenges. That’s where real transmission begins.

Could you give an example that illustrates the link between ore, mining, industry, and mineral heritage worth preserving?

Today, everyone has heard of lithium. In 2025, with the energy transition and the rise of electric vehicles, the idea of lithium mining is well established. But very few people could tell you what lithium actually looks like. Ask about gold or copper, and you’ll get immediate answers. Lithium, though, remains abstract.

And that’s exactly where the museum plays a vital role: reconnecting the public with the material itself. Explaining, for example, that chemical elements almost never occur in their pure form in nature. They’re most often found as part of minerals. Lithium is no exception to this rule: there is no such thing as “native lithium”. It’s found in minerals like spodumene, a lithium-rich silicate.

Spodumene has a dual identity: it can be mined for lithium, but it can also form stunning crystals. Its pink variety is called kunzite, a gem highly prized in the U.S. and Asia, though still largely unknown in Europe. These crystals, flat and striated, with nearly architectural shapes, are true natural wonders. They allow us to create a dialogue between science, beauty, and contemporary challenges.

A French example illustrates this point well. There’s been a lot of talk recently about a potential lithium mine in the Allier region, in the center of France. The plan would be to extract lithium from weathered granite rich in lepidolite – a lithium-bearing mica – to manufacture batteries for electric vehicles. But on site, there’s nothing visually striking, just decomposed granite. The upper layer is already being mined for its kaolin content.

At the museum, we show both: the ore (granite with tiny lepidolite crystals rich in lithium) and also large, well-formed lepidolite crystals from other locations. It’s these visually captivating specimens that grab attention and spark curiosity. And it’s through that beauty that we can communicate complex messages: about raw materials, how they’re extracted and processed, and the roles they play in our everyday lives.

Preserving mineral heritage isn’t just about keeping rare or beautiful objects. It’s about preserving memory: the memory of natural forms, structures, colors, and geological histories. And creating a conversation between that memory and today’s needs and uses. That’s where the museum finds its true purpose: in striking a balance between wonder, knowledge, and reflection on our relationship with Earth’s resources.

Are we currently witnessing a shift in how mineralogy is approached, collected, or presented? How is the museum adapting to these changes?

In Europe, when people visit museums, it’s usually art museums. Science museums, with a few exceptions like those designed specifically for children (such as La Villette), or the nation’s Natural History Museums, attract far fewer visitors. And when people do visit, they sometimes notice a certain lack of continuity: galleries that feel static, displays that haven’t been updated in years. In contrast, art museums often appear more modern, engaging, and dynamic.

At our museum, we’re fortunate to have a world-class permanent exhibition, renowned internationally for the diversity of mineral species on display. In terms of varieties shown to the public, we rank among the top five mineral museums in the world and our collection continues to grow. But today, the challenge isn’t just about the quality of the specimens. It’s also about bringing people back in, surprising them, engaging them.

That’s why we organize one or two temporary exhibitions each year. These are opportunities to offer fresh perspectives on the museum, attract different audiences, and build broader conversations. Some exhibitions create links with the world of art, though always with minerals at the core. Others are built directly around our own collection: we have nearly 100,000 specimens, of which only about 5,000 are on display. That gives us enormous potential.

And as a small, human-scale museum, we’re lucky to have a rare freedom to follow our intuitions and desires. That’s a real luxury! We can create exhibitions that are meaningful to us, that we enjoy building, sometimes even playful ones. Recently, we created an exhibit around the video game Minecraft, which is extremely popular with young people. The idea was to “de-pixelize” the digital world and reconnect it to reality. From the virtual blocks we extract in the game to real, tangible minerals. The response was overwhelmingly positive. We even had kids showing up proudly wearing their favorite Minecraft T-shirts to see the exhibit! It was a modest exhibition, centered around a dozen cases installed in the central space of the museum, with links to other samples displayed throughout the gallery.

Behind initiative like this is also a desire to bring to France some of the approaches I saw in the U.S. Over there, Natural History Museums are seen as places of living knowledge. Of course, they showcase Earth’s history, but they also address climate, resources, geopolitics, economics… You go with your family, at any age, because these are issues that affect all of us.

And I believe the Paris School of Mines is uniquely positioned to deliver that message. Here, we draw a direct connection between minerals and industry, between the natural world and the manufactured one. So it’s also up to the museum to adapt, by providing keys to understanding, to anchor our message in the present.

What we want to show here is that mineralogy is a living science, one that’s deeply connected to the major issues of our time, and more relevant than ever.

“Too often, science museums have remained stuck in a role inherited from the old “cabinet of curiosities.”

Museums are full of fascinating stories. Is there a particular anecdote you’d like to share that captures the richness and magic of this place?

Take our Minecraft-themed exhibition, for example. For that occasion, we selected specimens that represented the resources used in the game. Among them was an extraordinary native gold sample that hadn’t yet been on display… simply because it was preserved in a safe place of the School. And this wasn’t just any gold nugget but a rare, well-crystallized specimen, gifted to the School in the late 19th century by Paul Kruger, then President of the South African Republic. Until now, very few people had ever seen it. And suddenly, it reappeared… in an exhibition dedicated to a video game released more than a century later! That kind of contrast is what makes our work so exciting.

And that’s just one example. The museum is a place of memory. Behind every mineral, every label, there’s a story, a name, sometimes forgotten. It’s up to curators, but also curious visitors, to rediscover these sleeping treasures. Romain Bolzoni, our associate curator who joined recently, has brought to light several remarkable pieces that had been sitting in storage – rarer, more visually striking samples, or ones from localities that are now inaccessible. Some had never been shown to the public before.

Then there are the great rediscoveries. When I arrived in 2015, the museum’s director at the time, Didier Nectoux, pointed out a few cut stones discreetly displayed in a case. He said to me, “You know, in storage, we actually have some gems from the French Crown Jewels.” I’ll admit, I was skeptical as this information had remained very confidential. But one day, we opened the drawers, consulted the archives, cross-referenced old publications… and the evidence was undeniable. Yes, here at the École des Mines de Paris, we indeed held several historical lots from the 1887 sale of the French Crown Jewels! At that time, everything had been sold at auction and dispersed around the world, except for several sets preserved for their heritage value. One went to the Louvre, another to the National Museum of Natural History in Paris… and the third came here.

These include emeralds that adorned Napoleon III’s coronation crown, the last coronation crown in existence, which was melted down shortly before the sale. There are also gems that belonged to Marie-Louise, the second wife of Napoleon I: “Brazilian rubies” (pink topazes), and a set of amethysts that were once part of her jewelry. These are pieces of exceptional historical and aesthetic values, which remained unseen for over a century. It took time, and above all, generous private sponsorship, to bring them out of the shadows. Exhibiting such gems is no trivial matter: it requires rethinking security, designing custom display cases. Thanks to that support, we were finally able to present them to the public in 2016 and begin sharing their incredible story.

If you had to recommend three must-see books or places for mineralogy enthusiasts, which would you choose and why?

It’s hard not to start with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. It’s much more than a museum: it’s a collection of scientific institutions, free and open to all, that showcase science in all its forms. Among them, the National Museum of Natural History houses the world – famous Hope Diamond, which is actually the second most visited object in the world – after the Mona Lisa. That contrast says a lot: in Europe, the most visited object is a work of art; in America, it’s a rock! That speaks volumes about the cultural differences between France and the U.S., where science museums hold a central place in the collective imagination. And that’s their strength: they inspire vocations.

As for books, I can’t name just one – I’ve collected so many over the years. From Dana’s System of Mineralogy, which was one of my first “bibles” as a student, to more specialized works like The Nature of Diamonds, edited by George Harlow, or even accessible, discovery-focused books like Minéralogie enchantée, which actually sits right behind me in my office, there’s truly something for everyone.

But if there’s one message I’d want to share, it’s this: don’t stop at the surface beauty of minerals. As visually fascinating as they are, they are first and foremost scientific objects. Take the diamond, for example. It tells the story of the deep Earth. It’s the only mineral that rises to the surface unchanged. Olivine, pyroxenes, and all the other mantle minerals transform as they rise. Diamonds, on the other hand, remain intact. Formed between 1 and 3.5 billion years ago, it’s a true geological time capsule. A direct witness to the extreme conditions hundreds of kilometers beneath our feet. So yes, for me, the diamond is a scientifically fascinating object!

What I value most are places and approaches that present mineralogy in all its richness: scientifically, of course, but also artistically, historically, and aesthetically. In my office, there are as many specimens as there are photographs on display. Minerals lend themselves to multiple interpretations.

Unfortunately, in France, there are still very few places that fully embrace this diversity of perspective. In my view, what we need isn’t necessarily a single reference museum, but more exhibitions capable of weaving together all these threads, showing what minerals have to tell us, not just about nature, but about humanity as well.

Is there a person you would like to see interviewed as part of this series? And if you could ask him a question, what would it be?

I recently learned that Xavier Niel has a keen interest in the catacombs, and perhaps he knows that our School also has a historical and present link with this underground world… (it is a ritual of passage for our students – but shhh, this is a secret!).

He also clearly has a deep appreciation for Paris’s most beautiful buildings. The École des Mines, with its rich history, the extraordinary figures who shaped it, its architecture dating from the early 18th century and its remarkable museum, is without a doubt one of the capital’s most remarkable landmarks.

I don’t have any specific questions prepared, but I have a challenge for you: organize the interview here, at the museum. Let’s see if the magic of the place works!

Finally, we have a rather special question to conclude this exchange. You recently welcomed a new team member, Romain Bolzoni, to the museum and he’d like to ask:

“In a world without budget, time, or feasibility constraints, what would be your dream for the museum? What would your ideal museum look like? And in the real world, how can I help you move closer to that vision?”

So, let’s imagine this museum in a world without limits. We’re here in Paris, on the École des Mines’ historic campus. But the School has expanded: it now has other sites in Fontainebleau, Sophia Antipolis, and most recently in Versailles-Satory. Still, this Parisian campus is unique. It’s steeped in history.

We are housed in a former mansion belonging to the Duchess of Vendôme, built in the early 18th century. The School moved in at the beginning of the 19th century, and because the building wasn’t originally designed to host a school, major renovations were undertaken, especially starting in the 1850s. It’s from this period that the magnificent wood panelling, the enfilade-style rooms, and the prestigious staircase leading to the museum were created.

My dream? For this campus to become a true center of prestige. And for it to shine again with the splendor it deserves.

For example, I’d love to restore the original entrance, the one that leads up from Boulevard Saint-Michel to the museum. Today, visitors enter through a side door, almost hidden and not particularly welcoming. Back then, you accessed the building through a monumental staircase that led to a vast gallery, which in turn brought you to the “collections” including the stunning library, the mineralogy museum, and the paleontology collection.

“It was all designed to impress.”

In a perfect world, we’d highlight that 19th-century architecture again. We’d restore the original volumes, sightlines, and flow of the space. Above all, we’d return the museum to its full historical footprint. Today, it only occupies a small part of it. For example, the Salle des Colonnes (a 100-square-meter adjoining room) used to be part of the museum. It is now separated by a temporary partition and used as a meeting room, and a place to hold cocktails. It would be great to see the three aisles aligned again, and the view right through to the windows.

Another example: some of our offices are currently set up inside former exhibition showcases. That’s the case for Romain’s office! We had to move specimens just to make space for desks. Clearly, that’s not a long-term solution.

In this ideal museum, there would also be a real laboratory. As of now, we have no analytical equipment on-site here in Paris. For anything more in-depth, such X-ray diffraction, spectroscopy, or electron microscopy, we rely on partners at Jussieu or the National Museum of Natural History (rather than using facilities at our Fontainebleau campus). Even a modest lab, with something like an XRF analyzer, would be a huge step forward.

And why not make part of it visible to the public? A glassed-in space where visitors could see what goes on behind the scenes: cataloging, analyses, sample preparations… We could show that behind the display cases, real scientific work is happening.

We would also need outreach educators to run guided tours, children’s workshops, and create educational content, booklets, and perhaps even escape games. But above all, we need human resources. Our team is now small: only 4 permanent workers, (3 fully on site): two curators (Romain and I), one that takes care of opening the museum to the public (Marius), and one technical and administrative person (Farida). We are all full of ideas, but it takes people on top of money to make them happen…

And Romain, to answer that final part of your question, what you can do is help us carry this project forward. Help us raise funds, engage companies or donors who understand the value of this place. The key, as always, is funding: the kind that lets us hire people, even on short contracts for two or three years.

Reviving this museum, giving it the stature it truly deserves, it is possible. What we need are creators of ideas, energy, strong will… and a team that works well together, which we are fortunate enough to have already!