Minerals,

a whole world -

our entire world

The mineral world, a long and rich history

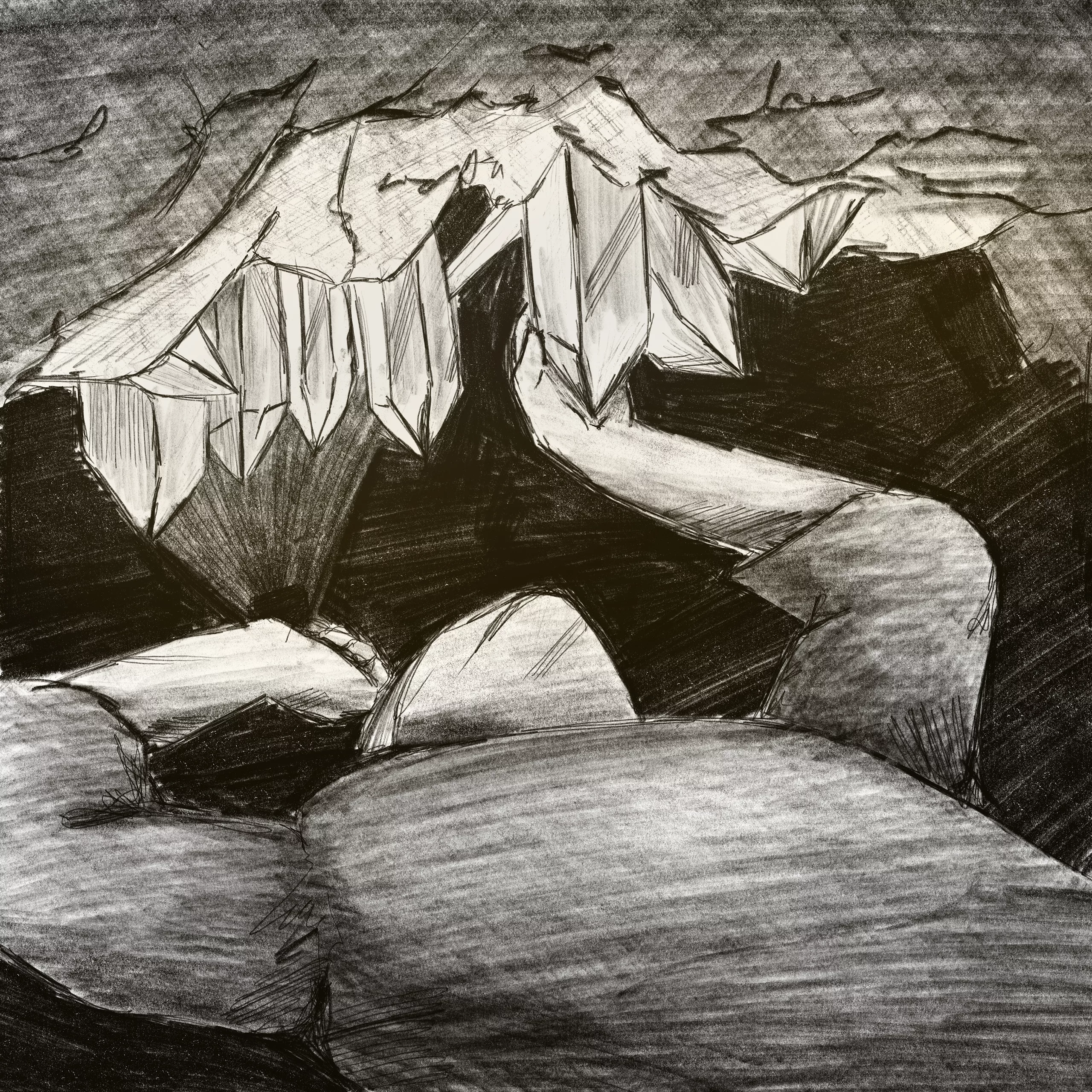

Since the formation of the solar system some 4.6 billion years ago, the Earth has been in a constant state of transformation. Spectacular volcanic eruptions and powerful earthquakes are just some of the most striking manifestations.

These phenomena have their origins in the fragility of the lithosphere, the rigid outer layer that envelops our planet. Composed of mobile plates resting on hot, viscous rock, the lithosphere is in perpetual motion, leading to collisions, fractures, and the deep subduction of tectonic plates.

These dynamics continuously shape our planet: oceans emerge while others vanish, mountains rise, and magma ascends through the plates, fueling volcanic activity. The oceans and continents we know today are relatively young. Around 250 million years ago, there was only one supercontinent: Pangaea. In a few tens of millions of years, the Mediterranean Sea will have disappeared, consumed by tectonic forces.

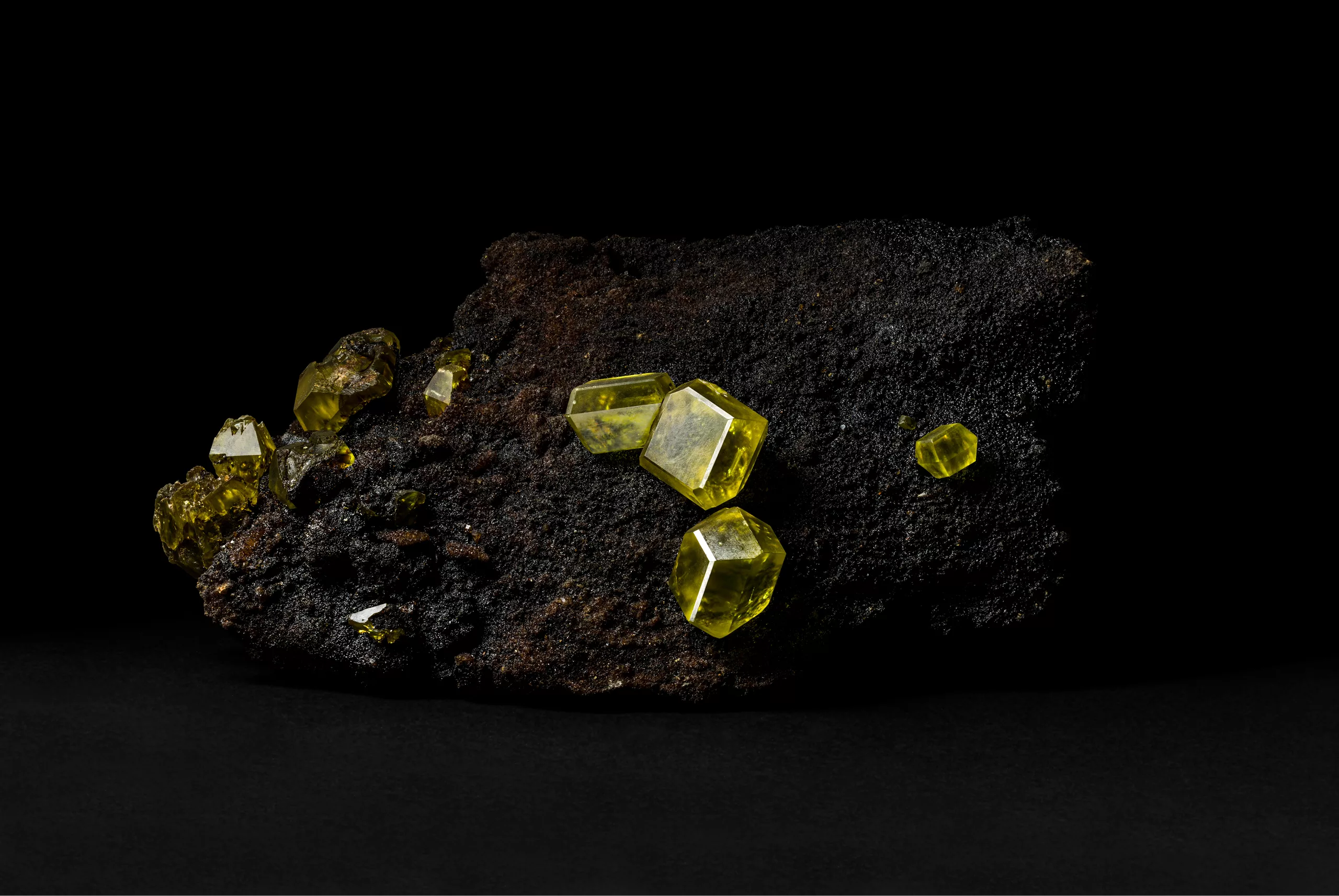

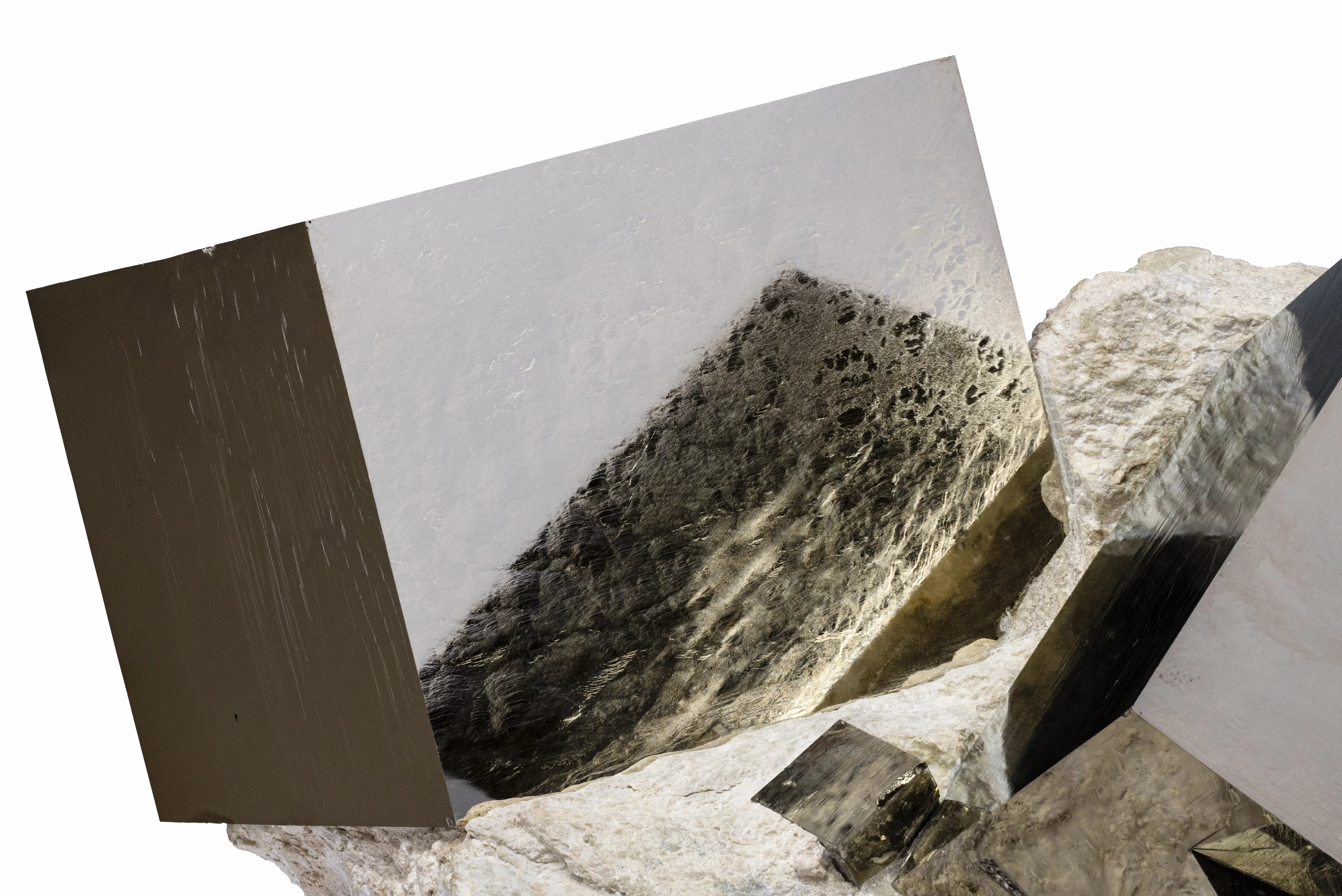

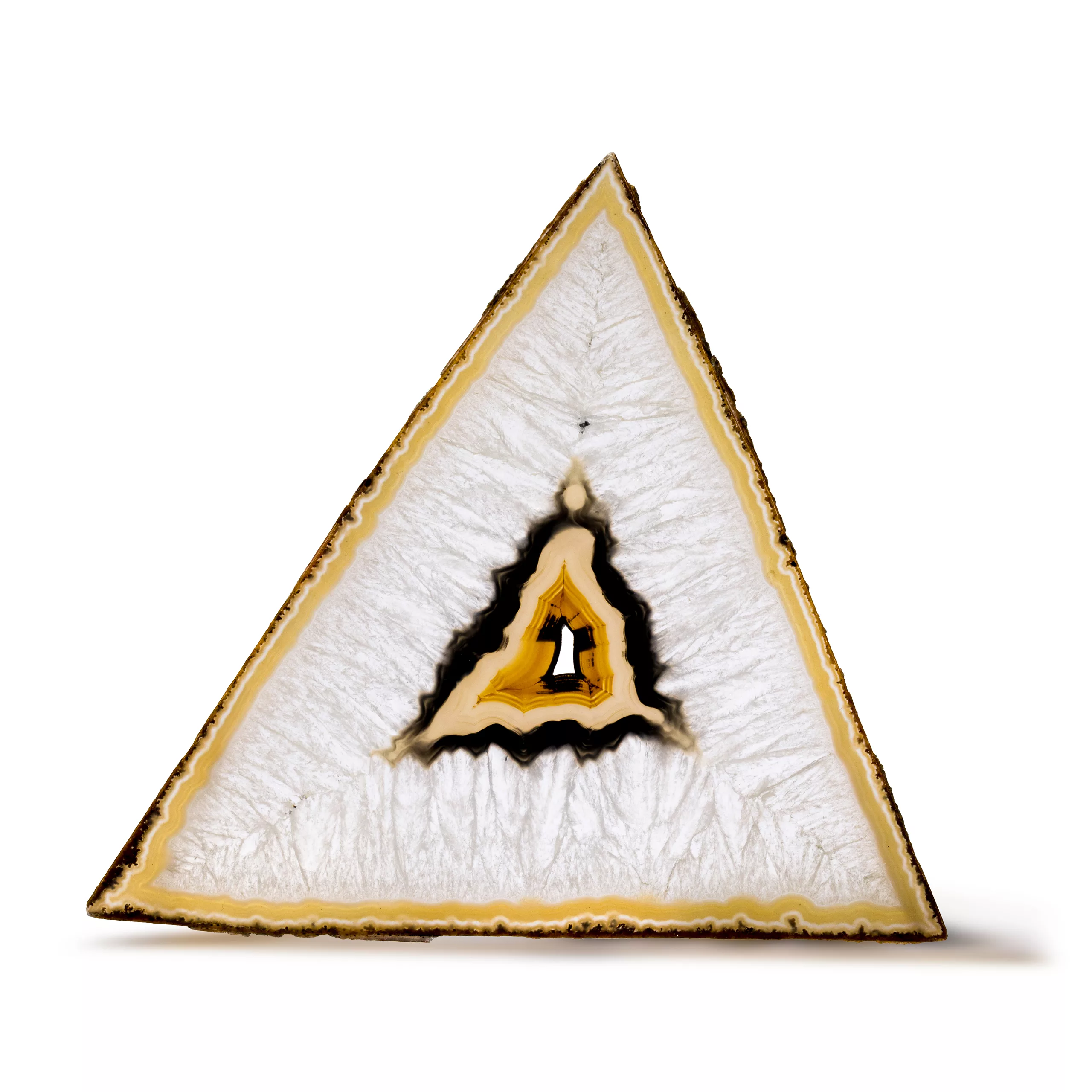

It is within this world of perpetual transformation that deposits and ore bodies form, where valuable, sought-after, or useful materials accumulate. Crystals are born in these environments: the most magnificent grow freely in cavities known as geodes, crystal vugs or, in the Alps, alpine fissures.

“Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed.”

Antoine Lavoisier

Conquering the mineral world

Of the three kingdoms of nature, the mineral kingdom remains the most enigmatic to us. It gradually revealed itself as humanity extracted from the depths of the Earth the materials that would shape its history.

“This dual mineral and cosmic condition of man.”

Eugenio Montale

It all began with the stones that prehistoric humans learned to shape into their first tools. Then came the moment when humans discovered that certain stones, when exposed to fire, could be transformed into metal, glass, or ceramics. The eras of chipped and polished stone were followed by the ages of copper, iron, and bronze. In medieval Europe, only seven metals were known, each associated with one of the then-identified celestial bodies: gold (Sun), silver (Moon), mercury (Mercury), copper (Venus), iron (Mars), tin (Jupiter), and lead (Saturn). From the late 18th century onward, discoveries accelerated, ushering in the era of light metals like aluminum, followed by uranium, silicon, and, more recently, rare earth elements. Today, nearly all stable metals have found a use: our smartphones alone contain almost fifty of them.

Alongside the conquest of metals, humanity has pursued a quest for precious materials, particularly stones. As far back as antiquity, they have fascinated us. In the oldest known epic, The Epic of Gilgamesh, written over three millennia ago, the hero journeys through a legendary garden where trees bear fruits of lapis lazuli.

Over time, other gems were added to this pantheon: red garnets, amethysts, and agates from Europe, diamonds from India, sapphires, rubies, and spinels from Ceylon and Burma. The 14th century marked a turning point with the cutting of diamonds, soon followed by other gems.

These precious stones became objects of display and symbols of both temporal and timeless power. Standing apart from ordinary materials and seeming to escape the ravages of time, they were believed to be eternal. They entered the realm of the marvelous, evoking enchantment, magic, and the supernatural.

From the Renaissance onwards, certain minerals became prized not only for their material value but also for their allure : native silver wires, emerald or quartz crystals fascinated by their beauty and natural perfection. The era of mineral collecting was upon us.

Object of wonder, object of knowledge

The mineral, an object of wonder

Is the underground world inherently hostile? Many kept their distance, convinced that no beauty could ever emerge from it. In numerous religious traditions, it embodies the underworld, while myths populate it with supernatural beings, often menacing: Kobolds in Germany, Goblins in France, or the fearsome El Tío in Bolivia – all guardians of hidden mineral treasures.

“The beginning of all sciences is the wonder that things are what they are.”

Aristotle

The sense of wonder became all the more striking when minerals from these depths are revealed. How can such perfection be explained? Is it truly natural? What hand could have shaped these forms? What alchemy could have given birth to these materials?

The curator of a major Parisian museum had developed the habit of starting each tour by clarifying that all the displayed minerals were presented in their natural state, without human intervention, except for a few slices of agate or tourmaline. Yet, without fail, the same questions would resurface at the end of every visit: “These stones weren’t all found like this, were they? The ones with flat, shiny surfaces must have been cut or polished?” Or more directly : “Who sculpted these stones?”

While the curator would always reaffirm their natural origins, he rarely admitted that this very sense of wonder – sparked by the perfection of their shapes – was one of the main reasons behind his passion. It is, after all, this initial fascination that often gives rise to the desire to collect.

“At the time, I didn’t know much about minerals, but I was intrigued by a cassiterite crystal. Trained as a chemist and Lebanese, I knew that this mineral contains tin, and that for many centuries, the trade of tin across the Mediterranean was monopolized by the Phoenician people.”

Salim Eddé

The mineral, an object of knowledge

Failing to understand the wonder inspired by objects means missing out on a fundamental richness: the ability to recognize all they have to offer us beyond that, what they have to teach us.

This lack of understanding carries even greater consequences in our modern civilization, which heavily relies on the material world, shaped by a science that emerged from the abandonment, at least temporarily, of philosophical and metaphysical frameworks. This shift allowed objects to be viewed as essential sources of knowledge.

From the 16th century onwards, the exploration of the natural world – especially minerals – became a significant pursuit. Naturalists and prospectors traveled across continents to collect them. A growing interest in raw, natural stones began to take hold. These specimens found their place in cabinets of curiosities – the famed Wunderkammern or “chambers of wonders” in Germany – which served as precursors to modern mineral collections.

Curiosity was soon followed by science, which became the main focus of exploration. In the 18th century, chemists and metallurgists began analyzing minerals, hoping to discover new metals or promising applications for science and industry.

This century saw the birth of crystallography, fully embracing the rise of rational sciences that would define the 19th century. In this context of discovery, knowledge collections multiplied, and collecting became a key method for organizing and disseminating these emerging knowledge.

It is therefore not surprising that two of the three oldest museums in France, after the Louvre, have their origins in natural sciences, and more specifically in mineralogy: the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris, founded in 1793, and the Musée de Minéralogie of l’École des Mines de Paris, originally created in 1794.

The latter, closely tied to this prestigious institution, stands out for its forward-thinking approach: minerals are collected not merely as remnants of the past but as promises of a scientific and industrial future.

A turning point came at the end of the 20th century, however, with the discovery of minerals of exceptional beauty, hitherto unsuspected. Interest in purely scientific collections faded in favor of an aesthetic approach, highlighting rare and precious specimens. The modern collector, heir to these two perspectives, now combines in-depth scientific knowledge with an aesthetic appreciation of mineral wonders.

Collectible item

The mineral, a collector's item

History offers numerous examples of the accumulation of precious objects. Reserves of value, they have formed the treasures of dynasties and temples since antiquity and still represent a significant part of household wealth today.

Why do we collect? Many answers, often tinged with psychoanalysis, have been proposed. But the answer seems simple: we collect for pleasure.

The collector is defined by the special attention they give to objects they consider “precious.” These objects stand out due to their rarity, value, beauty, or the desire and admiration they inspire. However, this perception remains subjective at first, as the collector’s taste evolves with experience and the growth of their knowledge. From the curious child to the great collector, wonder always comes before the desire to collect.

“Man is a being of desire, not of need.”

Gaston Bachelard

Through their choices, the affirmation of their preferences and the arrangement of the pieces they assembles, the collector can legitimately consider themself the creator of their collection. Their sensibility permeates each object, sometimes giving the entire collection such a strong identity that it becomes a signature. It is not uncommon, then, to see a piece described as « Property from Mr./Ms. X » at public auctions, a testament to the deep connection between the collector and their passion, their eye and mind.

Every collector, regardless of their field or means, is driven by the desire to find the rare gem, the object they deems unique. While some collecting fields rely on a structured market where pieces are often cataloged, minerals stand out due to their distinctive characteristics: natural origin, uniqueness, a rich diversity of forms and colors, and the constant discovery of new specimens.

Acquiring a mineral, a cultural act

Like art and luxury, collections are among the noblest activities of society: they gather their most remarkable achievements, reflect their deepest values, embody what they seek to preserve and pass on, and constitute a lasting legacy for future generations.

“The past belongs to us only if we pass it on.”

André Malraux

After World War II, the rise of the leisure society significantly broadened our cultural horizons, offering enthusiasts the opportunity to fully pursue their passions. Starting in the 1970s, the exploration of promising sites intensified, breathing new life into buried or forgotten locations, such as the famous mines of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines.

Major private collections began to emerge, and museum collections expanded. These developments are documented in increasingly captivating publications, celebrating the beauty and history of minerals, their deposits, and the most iconic specimens. A true mineralogical culture became an integral part of our collective heritage.

Collectors, who are the forefront of this discipline, are its key ambassadors. By acquiring high-quality minerals, they actively contribute to the preservation and enrichment of our cultural heritage. Non-collecting enthusiasts also play an important role.

In the United States of America, major benefactors quickly recognized the value of certain specimens from the mineral world – one that had so profoundly contributed to the nation’s wealth. Supporting the creation of mineral collections soon appeared just as essential, if not more so, than funding fine art museums.

Some major collectors

“For the collector, possession is the deepest relationship one can have with objects: not because they come alive within him, but rather because he himself dwells within them.”

Walter Benjamin

Is collecting minerals an investment?

Investment refers to the commitment of resources, financial or otherwise, in the hope of generating future value. For minerals, this approach is akin to long-term capital appreciation.

In 1995, when prominent telecom entrepreneur and stock market investor Barry Yampol was asked what his best investment had been, he replied without hesitation: « Minerals ! »

And yet, at the time, no one could have imagined the transformations that would overturn this market.

Prices for the most prestigious specimens – excluding precious materials such as gold and diamonds – were still in the six-figure range, and many collectors considered prices already too high, sometimes absurd, and predicted a market collapse.

Yet, history proved otherwise, as mineral collecting not only endured but flourished, driven by increasing demand and a growing appreciation for these natural wonders as both artistic treasures and financial assets.

Among the major upheavals, the boom in harvesting activities in countries such as China, India, Pakistan and Russia – joined by African nations such as Morocco and the Democratic Republic of the Congo – was accompanied by an improvement in extraction techniques and the development of restoration workshops. These advancements signaled the dawn of a new golden age for mineralogy, expanding access to exceptional specimens and elevating the overall quality of minerals reaching the global market.

The quality of the specimens reached unprecedented heights, prompting one Parisian curator to describe this abundance as “extraterrestrial mineralogy”, so inconceivable was the level of perfection he witnessed. Never before had such striking aesthetics and impressive dimensions been so widely publicized and photographed, allowing collectors and curators to compare specimens across different collections with ease.

Criteria began to emerge from the immense variety of known minerals that could be used to unanimously identify true mineralogical masterpieces.

At the same time, prices skyrocketed and the finest specimens, reaching iconic status, began to rival the financial benchmarks of other prestigious collecting fields such as fine art, rare gemstones and antiquities, solidifying their place as both natural wonders and valuable assets.

Even more modest collections, carefully curated, have seen their value rise, a phenomenon amplified by the covid crisis. The rise of online trading has opened up a market that was once the preserve of a select few, democratizing access to a passion that is now shared by a broader public. Today, mineralogy is an essential pillar of the world of collections.

“Nothing can ensure the protection of an object, whatever it may be, better than the high price it can fetch.”

Seymour de Ricci

La Haute Collection

Although the market is flooded with specimens, few meet the rigorous standards of Haute Collection. Admired and coveted, these unique heritage pieces attract the attention of discerning collectors, prestigious museums, and aware investors.

“The three most expensive words in any language were “unique au monde”.”

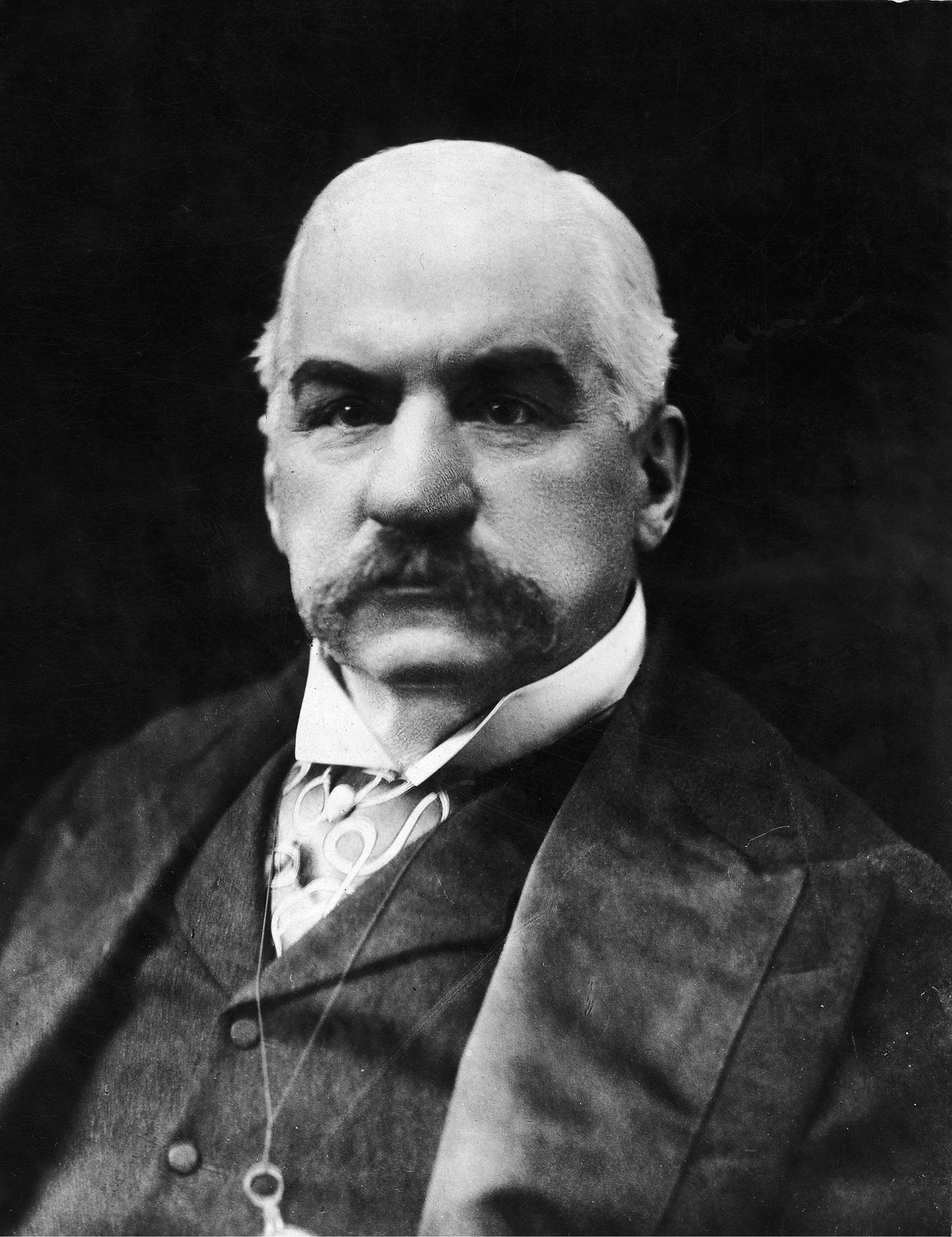

John Pierpont Morgan

But does one necessarily need a vast fortune to access the Haute Collection? The answer is more nuanced.

In fact, some modest collections can contain pieces worthy of this excellence.

There is no shortage of examples: a chance discovery in the field or an informed purchase can yield a specimen that meets the standards of the Haute Collection. This accessibility mirrors other fields, such as modern art, where visionary collectors acquired major works before their fame skyrocketed.

Collecting minerals is one of the few areas where it is still possible to obtain exceptional objects without unusual means. Consider the story of a French collector who, for a modest price, acquired a rhodonite from Chiurucu (Peru) that displayed noticeable alteration. After skillfully correcting this imperfection, he transformed it into one of the ten finest pieces known.

However, building a collection entirely dedicated to the Haute Collection of minerals requires a considered and ambitious approach. One of today’s greatest collectors, wealthy but a novice, was reluctant to embark on this field. His father, a collector of primitive art and coins, gave him two essential pieces of advice: «Always aim for excellence and surround yourself with the best.»

“Excellence does not result from a single impulse, but from a succession of small elements brought together.”

Vincent Van Gogh

Beyond the boundaries of collecting

Decorative object

Beyond collections, aesthetic minerals can be appreciated as decorative objects, enhancing prestigious interiors. Some specimens, of exceptional quality and value, rival those displayed in renowned museums.

From an industrialist who acquired twenty of the finest mineral specimens to adorn his company’s headquarters, to a famous French couturier showcasing impressive smoky quartz crystals in his home, minerals are increasingly embraced as striking decorative elements.

“In all the works of nature, there resides some wonder.”

Aristotle

Mineral, an "art d'objet"

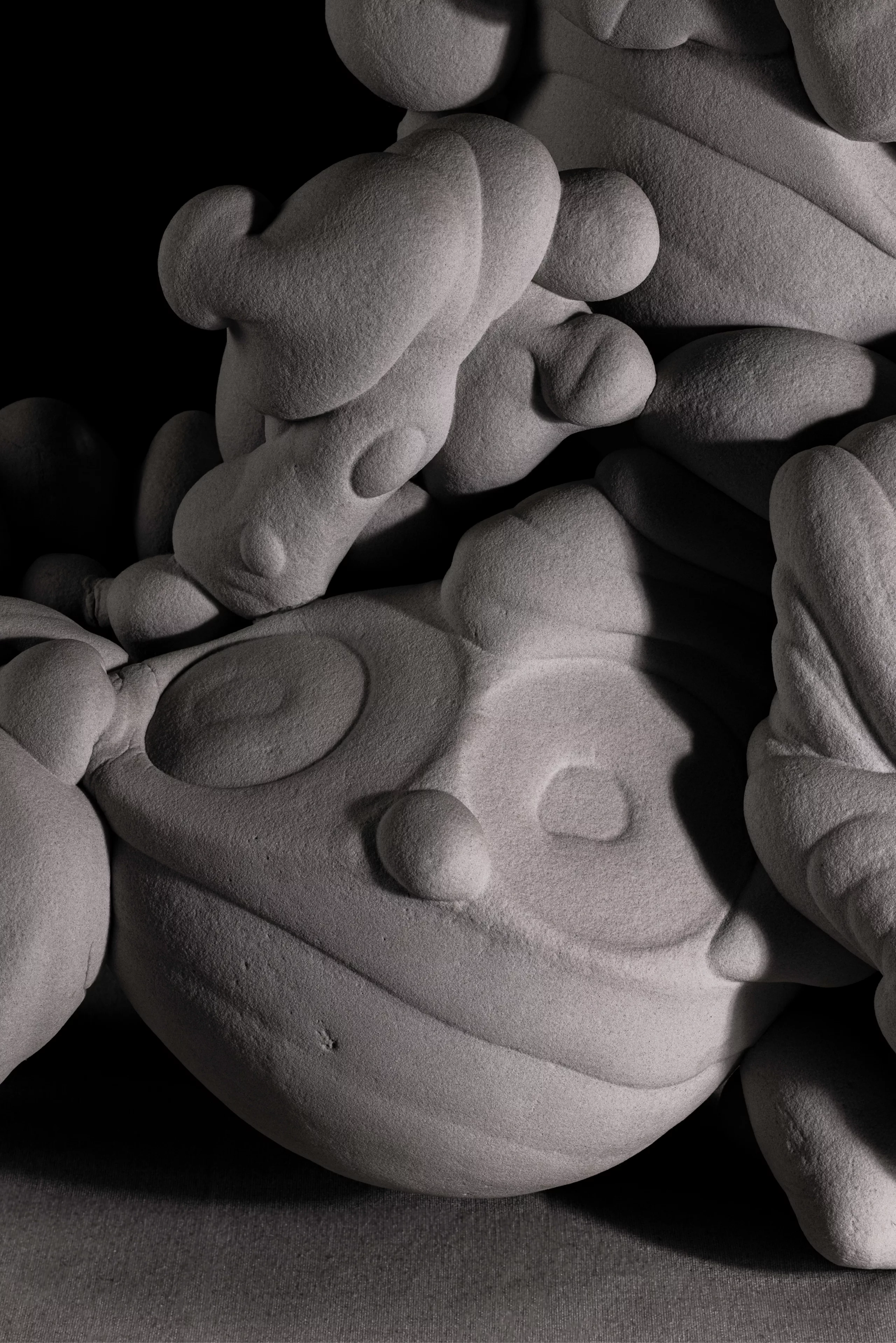

In its original definition, art is the creation of artifacts – objects crafted by human hands. Yet minerals, as natural beauties, have long served as a source of inspiration, even giving rise to literary works.

“No higher artistic teaching seems to me to be received than from the crystal.”

André Breton

André Breton (1896–1966), the father of Surrealism, devoted himself to studying the forms of crystals, while Roger Caillois (1913–1978) dedicated much of his writing to so-called “figured stones”, whose patterns rival the imagination of painters. Caillois observed and described these mineral formations as true works of art.

Though they do not belong to the category of Fine Arts, minerals have found a place within an artistic current that values the raw beauty of authentic natural objects.

It is an art without an artist. Without a signature. An art revealed by the eye of the admirer, the collector, or the connoisseur – one that can rival the most abstract human creations. The aesthetic appeal of a mineral, entirely untouched by human intent, unveils a raw, primordial beauty, leading some to define it as “the art of objects”.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks go to Jean-Claude BOULLIARD for his original text, whose words were the primary source, a precious material that we have tried to shape with care.

Our thanks also go to all those who have contributed to this content, whether directly or indirectly.

This illustrated text, including all written and photographs, is protected. Any use, reproduction or distribution, even partial, is strictly prohibited without the express written authorization of HBM.

Photo credits: please refer to Photos credits & legals.