Article published May 18, 2025.

Interview: HBM – Photo credits: © Louis-Dominique BAYLE

In the French mineralogical world, the closure of Le Règne Minéral – the magazine founded by Louis-Dominique BAYLE in 1995 – came as an unlikely earthquake. A true bridge between knowledge, science, and public passion, its disappearance raises serious questions about a shift that many consider detrimental to the entire field.

It seemed only fitting that for the very first interview in Terre Minérale, we offer the floor to him.

Our sincere thanks to this behind-the-scenes player for placing his trust in us, at a time when nothing seemed to suggest such an opportunity would arise so naturally.

Could you briefly introduce yourself for those who may not know you?

I founded the magazine Le Règne Minéral and served as its editor for 30 years. But before that, I was a complete unknown in the world of minerals – just a collector, one might say.

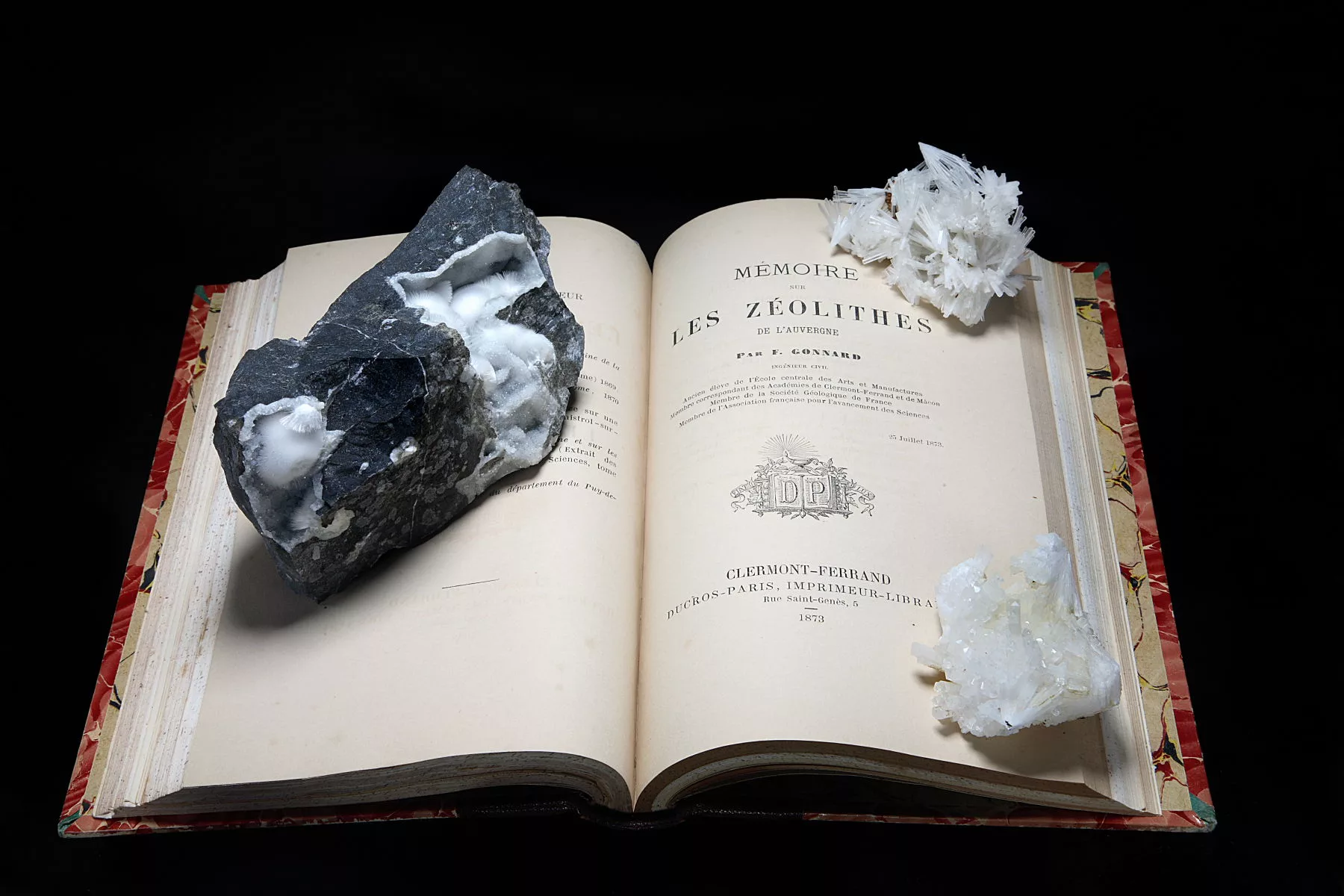

The magazine was launched on a whim at the beginning of 1995, although the idea had actually taken shape in 1993. It all started from a place of frustration – I found myself with nothing to read in French, although I was already a subscriber to The Mineralogical Record (United States) and Lapis (Germany).

I felt that there should be a dedicated publication in the country where mineralogy was born.

So I gathered a team of scientists, passionate amateurs and volunteers – and the adventure began.

The journey lasted three decades. What ultimately led to the magazine’s closure was the lack of cultural interest among a segment of French collectors, for whom a specialized publication was simply not a priority. As blunt as that may sound, many preferred to collect purely for enjoyment, without necessarily seeking to deepen their knowledge. Of course, there was a minority – inquisitive and devoted – who remained loyal to the magazine. They represented about one in ten collectors. A sad truth.

Do you collect minerals? If so, what draws you to this world?

Yes, I’ve been collecting minerals since I was a kid. I couldn’t give you an exact age, maybe 8 or 10 years old. My uncle and his family come from a plateau between Haute-Loire and Ardèche. Next to his farm, there was a plowed field where my young cousin and I often went for walks. For fun, we used to kick small pebbles as far as we could.

One day, I hit one as usual, but instead of flying away, it barely budged. Instead, my ankle took the full force of the impact: the stone was actually twenty times heavier than the others. When it flipped over, it revealed a stunning quartz crystal – about ten centimeters wide and fifteen high. And that’s when I was totally amazed.

I’d seen quartz before – the region is full of it – but something about that moment changed everything. That’s where it all began. Amusingly, even though I went on to become a mineral collector, quartz doesn’t particularly interest me, unless it takes on particularly unusual forms. But that first quartz still holds a special place in my collection – proudly occupying the symbolic slot number one!

It took me a few years to understand what truly attracted me to minerals. By the time I was 17 or 18, it became clear: the perfection of form and color.

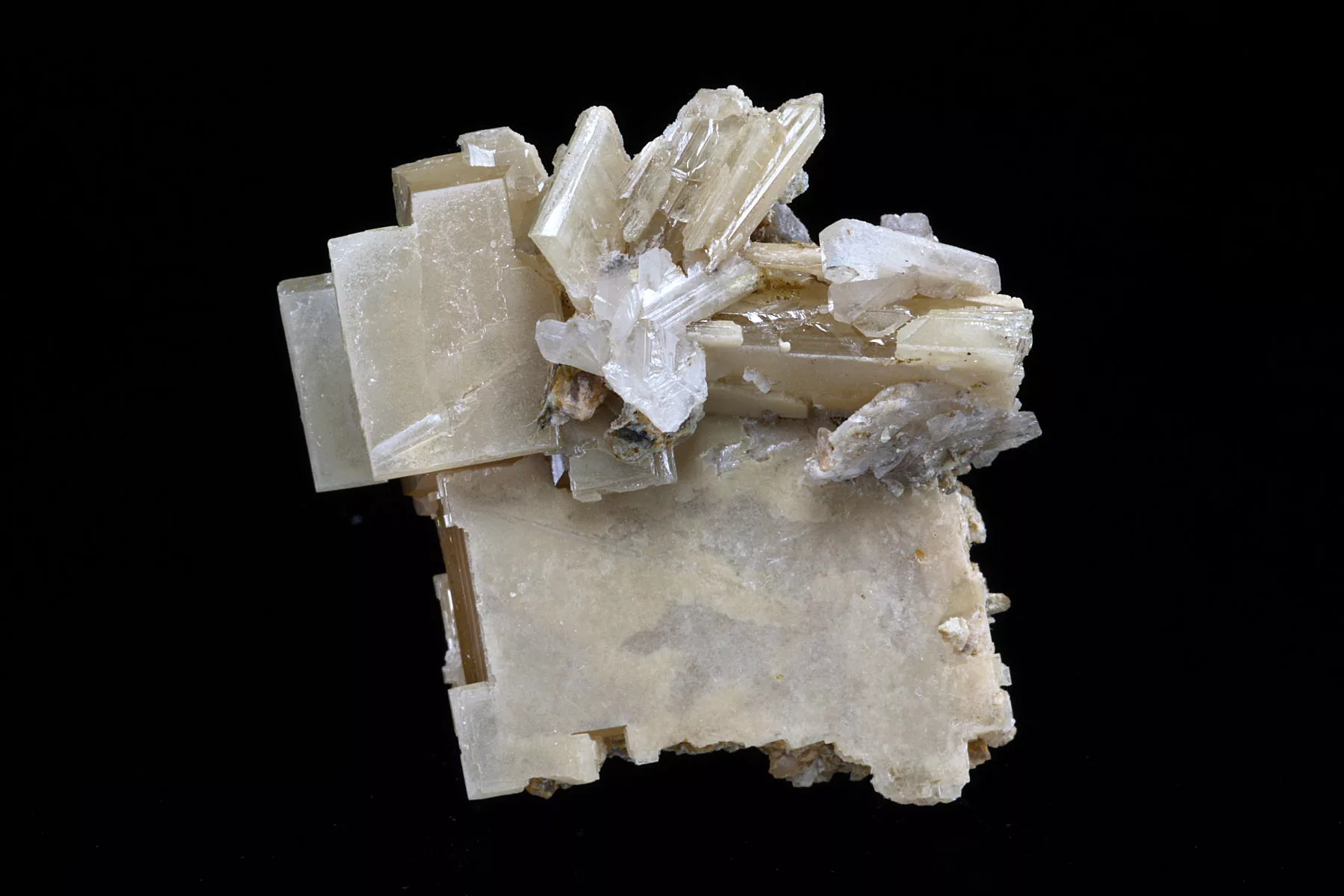

Unlike the plant or animal kingdoms, where everything is made of curves and softness – yes, some insects have angular shapes, but overall, living nature favors soft contours – minerals are all about angles, clean lines, and pure geometry.

Oddly enough, though I was never good at math, that kind of geometry fascinated me. It captivated me both intellectually and aesthetically, and sparked in me a desire to go deeper and deeper into the world of minerals.

To me, minerals aren’t just beautiful objects. I’ve always felt the need to intellectualize this passion. That reflective process is essential, it’s what gives my collection meaning and depth.

What’s your most memorable mineralogical experience?

I would say I have two truly unforgettable mineralogical memories.

The first one is tied to the Saint-Lucie site in Lozère, known for its stolzite crystals.

You might wonder : why would any average collector go searching for stolzite? Quite simply: because it’s a rare species. At the time, Jacques Geoffroy had written an article in Le Monde et les Minéraux on the subject, and as it just so happened that the site wasn’t too far from where I lived.

So, full of youthful enthusiasm, I set off. But I didn’t find much. And for good reason – as interesting as the article was, it turned out to be a little pipoté. The photos it featured did show stolzites… but not from Saint-Lucie. They were from Broken Hill, Australia, entirely different in both shape and color.

With my friend Christian Vialaron, we dug, scraped, and uncovered a few small crystals we thought were barites, frankly not very attractive. But in reality, they were stolzites ! We just didn’t realize it at the time, due to a lack of clear references.

A few years later, I met Yves Merchadier, one of the people who helped rediscover the mine, along with two colleagues. With a well-known team of passionate friends, we launched a proper excavation campaign and after twelve days, jackpot: we uncovered a series of pockets filled with truly magnificent stolzites.

Now that was a real adventure.

The second one involves the mythical tetrahedrite specimens from Irazein. With a small group of fellow enthusiasts, we set out to find these legendary crystals, known only in a few museums and now in a private collection.

We managed to locate the mine and began prospecting… but at first, nothing. Still, the experience itself was extraordinary: the excitement of the hunt, the spirit of exploration, and the camaraderie – that was already an adventure in itself. Then, after three days, everything changed.

A local resident, someone we had taken the time to talk with and befriend, showed us something remarkable: the finest known tetrahedrite, a 14–15 cm giant. It was engraved with the name of the original miner and the date of its discovery. We were speechless. The site is legendary, and while we only ever saw a single specimen, it was real — and right in front of us. It didn’t belong to us, but we had the privileget o see the best of it.

That, without question, is one of my greatest memories.

“Minerals are the stars of the lower worlds.”

Gaston Bachelard

So the field is important?

Going into the field isn’t just about searching and finding. Above all, it’s about sharing the experience, the camaraderie with friends. It’s a bit like those who explore catacombs: some go for the historical significance, others for the adrenaline, and others simply for the joy of being there, surrounded by fellow enthusiasts.

The life of a mineralogist without fieldwork? Unimaginable, in my opinion. The two are deeply connected. That said, because of my profession, I didn’t have many opportunities to get out there myself… But now that I’m retired, I fully intend to make up for lost time.

What do you see as the main changes in the market?

The mineral market is a complex world, where you’ll find everything from one-euro stones to specimens worth several million dollars. There are major collectors and more modest ones, each with their own approach.

I’ve been involved in this market for over forty years. My first show was in 1984, just as a visitor. Since then, I’ve seen it evolve dramatically. In the 1970s, it was estimated that France had around 100,000 collectors. Today, between 2000 and 2020, that number is closer to 15,000 to 20,000. The market has shifted, now heavily influenced by financial considerations.

For some, this financialization is a problem, as it has made certain specimens nearly inaccessible. But on the other hand, it has helped raise awareness about the importance of preserving the finest pieces. Let’s draw a parallel with the art world: if Picasso’s paintings had sold for just a few euros, perhaps they wouldn’t have been preserved, nor displayed in museums. The same applies to Rembrandt, Vermeer, and so many others. Their financial value played a role in their preservation and recognition.

It’s the same with minerals. A basic quartz worth one euro will remain a basic quartz. But a quartz from Arkansas, from La Gardette (Isère), a Swiss gwindel, or other exceptional specimens, possess a level of aesthetic and natural quality that earns them a place in museums and serious private collections. Their value also encourages miners and crystal hunters to extract them with greater care, unlike what was common practice 30 or 40 years ago.

Beyond that, the vision of mineralogy has also profoundly evolved over time. Collectors today are more demanding – damaged crystals, poorly formed pieces, or unremarkable specimens are less tolerated. Some collectors are driven purely by aesthetic criteria, others by systematics, and a growing number pursue aesthetic systematics – seeking the balance between scientific relevance and visual beauty.

Ultimately, this quest for perfection in minerals perhaps reflects our own vision of the world: a balance between order and imperfection.

Are we heading for a decline in enthusiasts?

Back in the 1970s, when I first became interested in minerals, mineralogy was still part of the school curriculum. My natural sciences teacher, as the subject was called then, was herself a mineral collector. I can’t thank her enough for instilling this passion in me. She used to show us specimens that I found absolutely fascinating: pieces of topaz, quartz, and even a few beautiful small crystals. Her collection wasn’t on display in the classroom, but it was carefully stored in a cupboard just next door.

At the time, there was a genuine enthusiasm for natural sciences. I had friends who, even if only briefly, were curious about minerals, botany, herpetology, even spiders… There was a broader culture of curiosity about the natural world, and our teachers played a key role in that. We were encouraged to create herbaria, we were shown a quartz found during a field outing…

It was a time when learning was rooted in observation, exploration, and being outdoors.

Also, back then, many mines and quarries were still active. Today, apart from a few remaining quarries, there’s almost nothing left.

Now, many of those early influences have faded, replaced by modern forms of entertainment – television, video games, and so on. Maybe that shift has led younger generations toward more passive engagement, whereas natural sciences demand an active mindset, nurtured curiosity, and a desire to explore. But I’m convinced there are still bridges to be built between those new habits and a deeper passion for the natural world. The desire to understand and explore is still there – we just need to help it resurface.

Do you think it’s still possible to start a collection today without a significant budget?

Yes, I’m absolutely convinced. Aiming for excellence can pose a financial challenge, but with curiosity, research, and reading – that thirst for knowledge that I hold so dear – you gain one of the essential foundations for collecting wisely. Without it, you miss out on thousands of things.

I remember a challenge I used to share with my friend Yves Merchadier. At the Munich and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines shows, we’d give ourselves a budget of 500 francs (about 80 euros today) to find three minerals worthy of being displayed. We played this game for several years, spending hours hunting down and comparing our finds – and it brought us immense joy.

Today, the market has changed. Maybe it would take 500 euros to do the same now, but I still believe you can find beautiful minerals for a few hundred euros – if you’re patient.

The key is to take your time. Don’t rush, don’t be greedy. Because while searching for one thing, you often discover much more… and that’s the true magic of collecting.

If we were talking to a novice audience, what advice would you give on how to train their eye and start a collection?

Can I be honest? The mineral market is one where you have to know how to navigate. It’s a game between seller and buyer.

But just like in the art world, where thousands of artists create hundreds of works, mineralogy produces millions of specimens each year across the globe. And within that vastness, you have to know how to look, to spot the truly unique pieces, those that stand out through rarity, beauty, or story. As I said earlier, knowledge is key.

Shows like Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, Munich, and a few smaller events – although increasingly rare in quality – remain valuable places for exchange. But without knowledge, it’s much harder to make informed choices, and you run the risk of being guided only by the dealer’s sales pitch.

Once you’re holding a stone in your hand, curiosity takes over. Many people now turn solely to social media, which can lead to misinformation. Others, more cautious, look to reputable dealers, scientists, museum curators, or reference books, often written by experts on a specific locality or species.

And that’s where everything shifts: it becomes intellectual. A collection without reflection is just a full display case, with no soul and no real value. I’ve seen many average collections, but also some extraordinary ones – not always from wealthy collectors. Some people with modest means have built fascinating collections, because they are thoughtful, curated, alive. That’s why it’s important to surround yourself with the right people and never fall into compulsive collecting.

Which books to buy?

If you had to recommend three books on mineralogy, which would you choose, and why?

Three? Gosh, for me, it would be dozens! That’s exactly the problem. But all right, let’s go ahead and pick three.

The first is the guide by Julien Lebocey. In my opinion, it’s probably the best guide in the world for collectors. This was an idea I had in mind for over twenty years: to create a true reference guide. There were already some collector’s guides out there, but they were outdated – mostly rewrites from the 1970s or ’80s. When I hired Julien in 2007, we started discussing it, and I proposed we bring the idea to life. He dedicated seven to eight years of work to it. What surprised me was its international success. Even though it’s only published in French, it’s sold worldwide – thanks to its exceptional photography, combined with thorough, well-documented content. I personally designed and laid out the book over a span of 14 months, trying to make it the book I wish I’d had at 14, 15, or 16. A guide that would’ve saved me from many mistakes and helped me move forward much faster.

The second is American Mineral Treasures (2008). This book showcases the finest American localities, in a very American style! If there were a French equivalent, I’d be shouting Cocorico! It’s a stunning work that celebrates the mineral richness of the United States and in my view, a book like it should exist for every country. Unfortunately, it sold out within just a few months.

The third is a book I also published – but that’s not the reason I’m choosing it. There are so many brilliant books I could mention. But Christophe Lucas’s book truly stands apart. It’s unlike anything else. His project: to present the 50 finest fluorite localities in France. And most importantly, it doesn’t stop at mineralogy, it explores the human stories behind each site. Each location is described in detail, sometimes across multiple pages, and accompanied by the testimony of a key figure: a high-hand collector, a museum curator, a scientist, a high-level collector, a specialist publisher, an artist working with minerals in mosaics, or professional crystal hunters and dealers. These voices come from vastly different worlds – some even in conflict with each other. And yet, each of them brought their vision, experience, and passion to this book. That’s what makes it a truly unique, timeless, and deeply human work.

In your opinion, what does the future hold for mineral collecting?

I’m no Madame Irma – no crystal ball here! (laughs)

I’d love to see mineralogy continue to thrive, even if, from my perspective as a former magazine editor, its evolution raises real challenges. The slow disappearance of mineral publications raises serious questions about how knowledge will be passed on – and I wasn’t the first to go through this, four other titles shut down before mine, meaning half the world’s mineral magazines are now gone.

This makes the role of dealers more central than ever and it’s crucial that they continue to offer a diversity of accessible specimens to sustain curiosity and inspire collectors. The future of mineralogy will depend on maintaining this balance between the market, passion, and knowledge-sharing.

But there’s reason to be optimistic.

Elitism has its virtues : it pushes things forward, gives us new ways of seeing. Top collectors have helped elevate the market, and dealers followed. Naturally, this drove prices up – even for mid-range and entry-level specimens, which are now harder to access for some collectors. Often without real justification. Food for thought.

Since COVID, the market has shifted significantly toward online platforms, opening up new opportunities for a younger generation of collectors and enthusiasts. Their approach is different: they buy online, they share on social media, and they attend shows with a new mindset. This transition has energized mineralogy, expanding its audience and attracting a more diverse, international community. That said, with an avalanche of information – reliable or not – there’s always a risk that the majority, naturally curious but often inexperienced, may be easily influenced.

One thing that really makes me happy is seeing a growing number of knowledgeable female collectors. They tend to be discreet yet insightful, and they bring a refreshing energy that our little world truly needs!

Also, the preservation of exceptional specimens remains a top priority and is vital to our mineral heritage. Museums play a key role in passing on this passion. They are often the spark that lights the flame: when a child sees minerals in Paris, London, or New York, it can be the start of a lifelong fascination. As Gaston Bachelard once said: “Minerals are the stars of the lower worlds”. How true and beautiful this phrase is!

Is there someone you’d like to see interviewed in Terre Minérale? If so, what would you ask them?

It’s hard to name just one. If you’ll allow me, I’d like to name three.

Louis Durand (1919–1994) is my mentor. He taught me so much, even though I only knew him for about ten years. But in those ten years, he awakened my passion. Before him, I was like a flower in bud, not quite ready to bloom. And then, that meeting changed everything. When I told him about my project in 1993, he said: “You’re going to crash and burn. It’s not viable. But I’ll help you”. And I did it – thanks to him, and in a way, without him, because he passed away in 1994, right at the beginning of the project. To this day, there are a thousand questions I wish I could ask him. Questions that I miss. Forty years after his death, I still miss him. He will always be a spiritual father to me.

Then, there are two people I’d love to see interviewed.

First, Salim Eddé, in Lebanon. I have a special connection to that country, and I believe he’s perhaps the one who intellectualizes minerals more than anyone else. If I had to ask him just one thing, it would be: “Could you imagine a collection without zircon?”

And then, Federico Pezzotta. With him, it wouldn’t be a question so much as… I’d just want to say thank you. Because he’s a remarkable man. He’s built a bridge between science, amateurs, field collectors, and labs. I wouldn’t even know what exactly to ask him – but I’d love to learn more about him, through your questions.