How to approach the minerals

An introduction by Jean-Claude BOULLIARD

Every true enthusiast seeks to express their personality through their acquisitions – to leave a mark, a sense of taste, a unique signature. There is no universal or standard way to collect: the one that resonates with the collector is, by definition, the right one.

That said, once a certain level of demand is reached, it becomes essential to consider a number of objective criteria.

Unlike other types of collections, where items may be catalogued and counted, the world of minerals is one of absolute individuality – no two pieces are ever quite the same. This diversity makes it essential to refine one’s eye, taste and discernment.

The qualities attributed to fine specimens are based on evolving standards of beauty, knowledge, and rarity. These references are shaped by the exhibition of prestigious pieces, major international fairs, and the expertise passed on by museums and specialized dealers.

Some misjudgments, however well-intentioned, can limit the potential of an entire collection, even when significant resources are involved. A well-known anecdote illustrates this point: a collector once acquired a superb group of danburite crystals from Mexico from a unique find, only to return it to the dealer, deciding it was too large for his taste. He instead opted for some Australian gypsum crystals: aesthetically common and of modest value. This example reminds us that ignoring established criteria can sometimes lead to unfortunate choices.

High-grade minerals meet a wide range of criteria that need to be understood. These are divided into two groups: quality and cultural criteria.

Quality Criteria

An obvious vision

Quality criteria are first and foremost obvious to the eye. From antiquity to the present day, the intrinsic characteristics of the material have served to distinguish precious stones from ordinary rocks: color, transparency, luster, and size form the foundation of this perception. In the realm of mineral collecting – where specimens are untouched by human hands – additional criteria come into play, specific to the natural singularity and inherent value of each piece.

Color

A rich and nuanced vocabulary, often borrowed from the world of gemstones, is used to describe our perception of color, and many minerals reveal a chromatic range of remarkable diversity. Some, such as tourmaline or fluorite, are even affectionately known as «rainbow minerals».

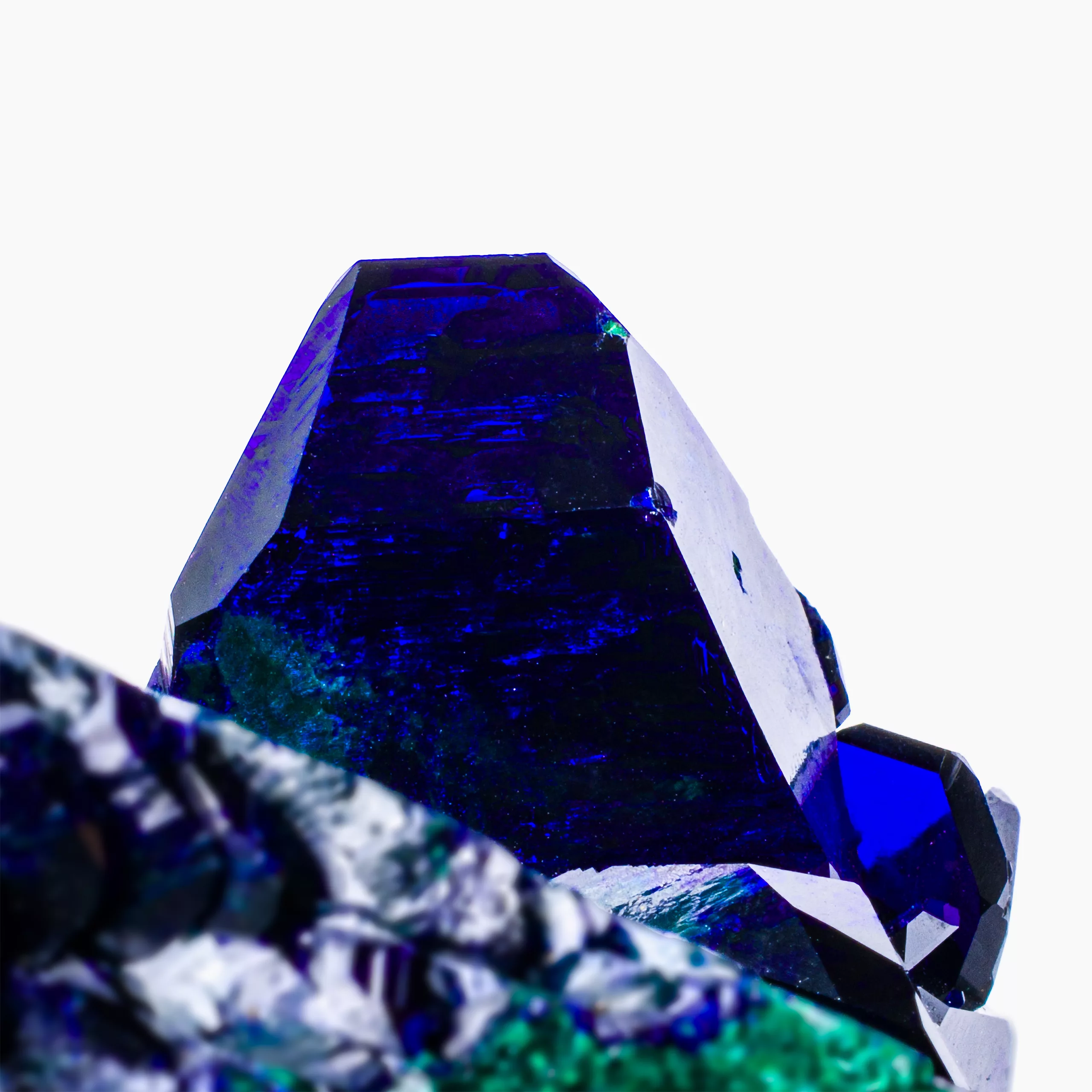

For transparent specimens, vivid, saturated hues hold particular appeal. Over time, a natural hierarchy has emerged, with red, the symbol of rarity, traditionally at the top, followed by pink, blue, green, orange, yellow, and purple. Certain rare and captivating shades of blue and green can, however, transcend this traditional scale.

“Color in itself expresses something. One cannot do without it.”

Vincent van Gogh

Shapes

A harmonious and well-structured arrangement is essential, avoiding any sense of disorder or confusion. Slender, airy forms of singular beauty are particularly prized, captivating the eye and enhancing the natural aesthetics of the mineral.

A specimen is distinguished by the precision of its crystals, revealing the full richness of its formation. Complex terminations, when elegantly developed, further enhance the rarity of the specimen.

Transparency and Purity

Transparency, a fundamental criterion, refers to a crystal’s ability to allow light to pass through it. The most prized specimens are characterized by their remarkable purity, ranging from flawless clarity to slight translucence, depending on the inherent properties of each species.This pursuit of excellence is embodied in the term gem quality, referring to minerals whose brilliance and transparency rival the finest cut gemstones.

A crystal that is too dark to let light through may lose some of its appeal. Conversely, certain natural inclusions, far from being imperfections, enrich the identity of fine mineral specimens. Famous examples include dioptase or dumortierite included in quartz, or a garnet suspended within diamond. Such specificities tell the story of the mineral and endow it with a distinct character.

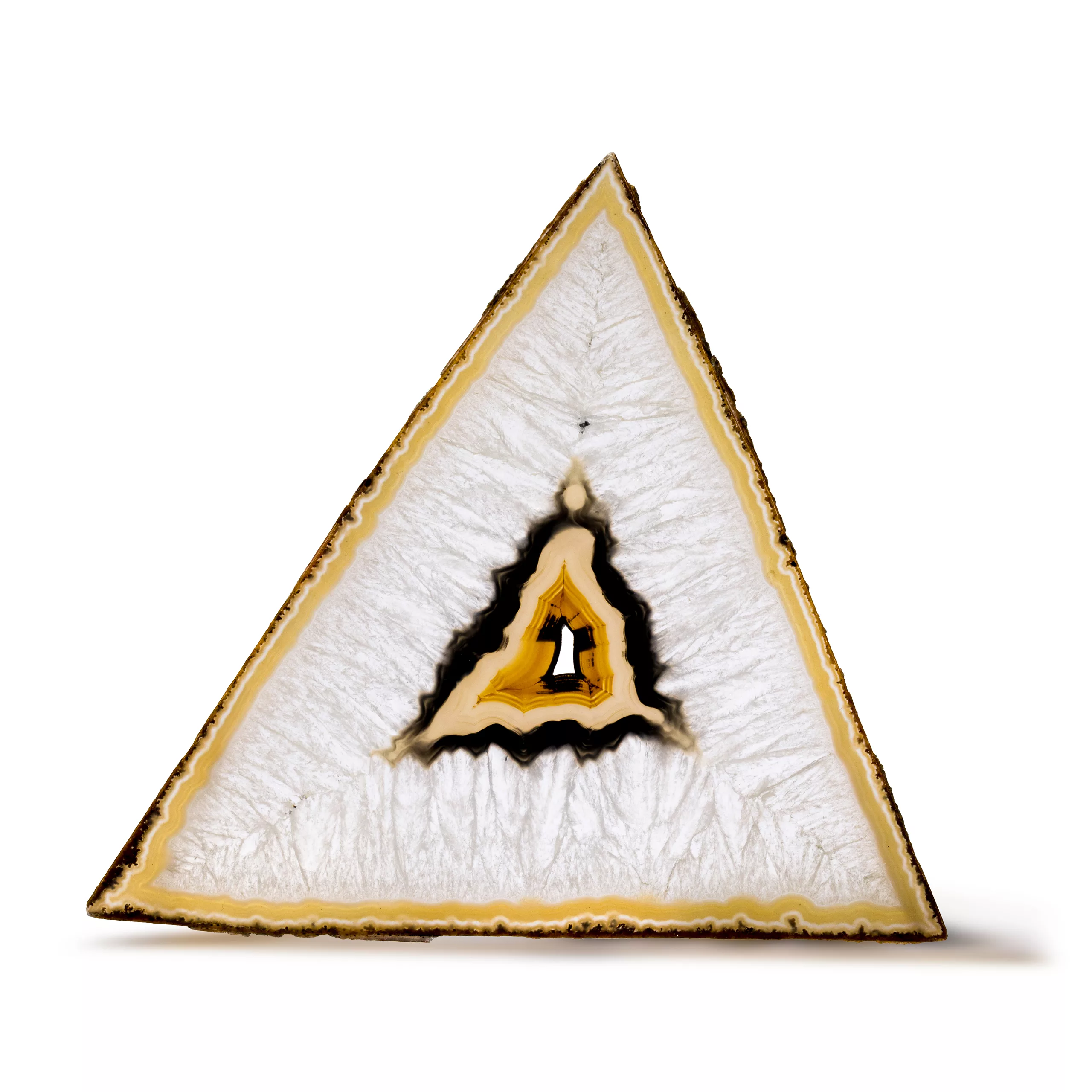

Sometimes, a thin layer of another mineral becomes integrated during a crystal’s growth, revealing, in the final specimen, the silhouette of a former stage of its development – a phenomenon known as a phantom crystal.

“The word ‘pure’ has yet to reveal its true meaning to me. I am still quenching an optical thirst for purity in the transparencies that evoke it, in bubbles, in dense water, and in imagined, unreachable places within a thick crystal.”

Colette

Luster

Luster is a decisive factor in evaluating the quality of a specimen, reflecting how light interacts with its surface. A bright, reflective appearance is generally preferred over a dull one, particularly in transparent crystals, or in opaque minerals such as sulfides and certain oxides, where luster plays a key visual role.

That said, less lustrous surfaces can also be prized when they highlight a unique texture – as in the case of fibrous malachite – or when they create a contrast that enhances an essential part of the specimen.

Perfection

The condition of a specimen is a major criterion, often determining its standing or prestige. Visible imperfections, such as breaks, chips, or cleavage, tend to diminish a specimen’s value. Conversely, certain natural features, such as “contacts” (areas where a crystal grew against another), are generally accepted, provided they do not disrupt the specimen’s overall visual harmony.

“Details make perfection, and perfection is not a detail.”

Leonardo da Vinci

Few people, apart from certain dealers and a few collectors and curators, truly master the valuation of fine minerals. Among them, David Wilber, a prominent figure in the United States during the 1970s, made a lasting mark with an exceptional collection before becoming a renowned mineral advisor to private collectors. He established rigorous standards, valuing above all perfection: specimens with no breaks, chips, or visible flaws – now referred to in the field as “Wilber specimens.”

His high standards even led to the identification of minor imperfections, nicknamed “micro-Wilbers” and “nano-Wilbers.”

These ultra-strict criteria have since been revisited and softened with the rise of modern techniques in repair and restoration.

Perfection: Repairs and Restoration

The practice of repairing, restoring – even enhancing – mineral specimens is not new. It dates back to the 17th century, when natural minerals first began to capture the attention of collectors. It was said that Alpine crystal hunters would gather minerals during the short summer season, then “restore” them throughout the long winter months. Similarly, English and German miners were known to reattach broken crystals or fix specimens to their matrix. In many cases, both the workshops and the restorations themselves remained carefully concealed.

“The only thing that cannot be embellished without being destroyed is the truth.”

Jean Rostand

By the late 20th century, recognized and respected mineral restoration studios had emerged. These workshops now disclose all interventions and employ advanced techniques, some borrowed from prosthetic dentistry, others from archaeological, antiquities, or fine art conservation, and some developed exclusively for mineral specimens. This modern approach is reminiscent of fossil restoration practices, used to preserve and bring back to life extraordinary pieces that might otherwise have been lost.

A striking example comes from Brazil, where geodes containing tourmaline crystals often collapse during extraction. For many years, only loose crystals or the rare intact groups were preserved. Today, dedicated teams work with the care of archaeologists, collecting every fragment of a fallen geode, cleaning, photographing, and cataloging them before beginning the long and meticulous process of reconstruction.

Beauty / Aesthetic Appeal

“To live, every man needs aesthetic ghosts. I have pursued them, sought them, hunted them.”

Yves Saint Laurent

Minerals often present themselves through naturally occurring forms and arrangements that reveal varying degrees of refined aesthetic expression.This is wheret the collector’s artistic eye truly emerges. To define aesthetic criteria too literally or analytically is, in some sense, to devalue the very essence of a mineral’s beauty. The minerals themselves are their finest ambassadors.

Contrast

When we talk of fine mineral collecting, a specimen often consits of multiple crystals – a well-formed mineral resting on its matrix, or a harmonious association of different elements. In such cases, the arrangement must allow each crystal to stand out without overshadowing the others. A well-balanced contrast – whether in color, texture, or structure – is essential to highlight the different elements of the specimen and make it “readable”.

“Love generally prefers contrast to similarity.”

Honoré de Balzac

Scale and Weight

In the mineral world, large, perfectly formed crystals are especially sought after, their rarity setting them apart from smaller specimens. Yet for a long time, collectors followed an unspoken rule: a fine mineral should remain manageable by hand, typically weighing between five and ten kilograms. Some connoisseurs even favor small, exquisitely detailed specimens, while larger pieces – often over forty centimeters – are seen more as decorative or contemplative objects.

This perception, however, has evolved over the past few decades. Technical advances in the last thirty years have dramatically changed the landscape, allowing for the extraction of monumental specimens, some measuring a meter – even up to five meters – in height. These spectacular pieces, striking for both their scale and visual impact, have now found their place in museum collections and among visionary private collectors.

As early as the 1980s, The National Museum of National History in Paris led the way in exhibiting large-scale mineral specimens.

More recently, in 2018, the MIM Museum in Beirut acquired a four-ton quartz crystal group, further confirming the growing appeal of these monumental mineral works.

Cultural Criteria

Science and Species

Cultural criteria fall into two main categories. The first is grounded in science: mineralogy, crystallography, geology, and deposit typology. The second is based in history, including the geographic origin of the specimen and, increasingly, its provenance or pedigree.

“Crystals are the Earth’s archives.”

Gabriel Delafosse

Science and Species

With the birth of crystallography in the late 17th century, mineralogy emerged as one of the first truly modern sciences.

The field experienced major advances throughout the 19th century, revealing extraordinary richness and giving rise to numerous scientific branches. Each major discovery has opened new chapters in our understanding of the natural world.

Mineralogy laid the foundation for inorganic chemistry, crystallography, crystal chemistry, condensed matter physics, and crystal optics. More recently, it has played a central role in disciplines such as geochemistry, cosmochemistry, ecology, archaeology, and gemmology.

Today, mineralogy continues to evolve, paving the way for emerging fields such as biomineralogy, the bridge between the living world and the mineral world.

Trends

Rather than speaking strictly of trend, it is more accurate to refer to the major sources of mineral specimens, whose prominence tends to shift over time.

In the 19th century, the main deposits were in the Alps and the metal mines of the UK, Germany and Austria.

In the 1970s, the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show in Arizona became a landmark event, drawing extraordinary specimens from Mexico, Brazil, Peru, and Bolivia. At the same time, Afghanistan and Pakistan sparked significant interest with pegmatite minerals – now highly prized by collectors.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, there was a surge in Romanian and Russian minerals entering the market, before the market stabilized.

By the end of the 20th century, China emerged as a powerhouse, producing spectacular specimens that reshaped the market.

In recent years, however, increased domestic demand has made Chinese material more scarce, to the point where some Chinese dealers are now actively acquiring fine specimens from Europe and the United States.

“Fashions fade, style is eternal.”

Yves Saint Laurent