Article published July 25, 2025.

Interview: HBM – Photo credits: © Mineral & Gem / Stephanie Joplin / A. Certain – HBM

With 45,561 visitors and a prestige exhibition widely acclaimed, the 60th edition of Mineral & Gem reaffirmed its standing as a major international event. Step behind the scenes of this one-of-a-kind gathering in the Val d’Argent through the eyes of Thomas Bellicam, CEO of the organization and a child of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines.

To start, could you briefly introduce yourself to our readers and tell us about your connection to Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines?

My name is Thomas Bellicam, and I’m almost 33. I’m a child of the valley of the Val d’Argent and I grew up in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, though I wasn’t immersed in the world of mineralogy from a young age.

One of my grandfathers worked for the local municipality. Among other things, he was responsible for opening up forest paths. In doing so, he stumbled upon several old mines. It wasn’t exploration in the true sense, but his job led him to uncover some of them. Did he pass that passion on to me? I couldn’t say.

My background is a bit unconventional. nothing predestined me toward to become the organizer of the Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines show. But when you grow up here, in the Val d’Argent, you live to the rhythm of Mineral & Gem. I first discovered the event during middle school, through the school’s sports section under the UNSS (National Union of School Sports). Every year, students helped run a refreshment stand in the high school courtyard, right beneath the sequoia tree. The money we raised went toward sports projects like competition trips or new equipment. It made those activities more accessible.

I can’t remember the exact year of my first participation, but my childhood memories are still vivid. Back then, before security measures were tightened, the Monday after the show, while exhibitors were packing up, local kids would gather in the aisles. It wasn’t official, but everyone hoped to find forgotten minerals, fragments of broken geodes, sometimes even intact specimens. It was a real treasure hunt. Every year, we’d head home with little baskets full of quartz, amethysts, and stone fragments.

I also remember once finding a meteorite about the size of a two-euro coin. Memories like that shaped my connection to the show long before I understood its full scope.

How did you come to play a key role in the organization of Mineral & Gem?

After middle school, already quite involved in local community life, I started working at the GEM site, at the ticket booth. We were in charge of the cash desks, and over the years I became the go-to person at one of the ticketing points. That’s how I first got involved as a volunteer in the event.

It was around that time that Michel Schwab announced the relocation of the show to Colmar. I was in photography school at the time. My academic background had originally followed a science track -I earned a science High School diploma (baccalaureat), mostly by default, on the advice of teachers who emphasized its possibilities. But it wasn’t really a choice of passion. I was fascinated by meteorology, but math and science weren’t my strengths. After finishing high school, I switched to photography, earning a vocational certificate (NVQ) followed by a BTEC. Since I’d already completed the general education requirements, my schedule was more flexible.

I saw the relocation of the show as a major loss for Sainte-Marie. So when Claude Abel, the mayor at the time, expressed his desire to keep the event in the town, I reached out to him on my own initiative to offer my help. He later told me he’d received very few calls at that time -and that I was one of the very first to step forward. I spent a year managing the event’s social media presence.

The following year, Mineral & Gem’s first edition, I joined the “Red Vests” team. By then, I had finished my studies: I’d earned my photography diploma and had been accepted into a BTS (advanced vocational training) program at Auguste Renoir in Paris (one of the top schools in the country). But the project didn’t win me over. Life in Paris felt out of reach, the cost of living was high, and the 16th arrondissement was worlds away from what I knew. My family, modest in means, didn’t qualify for scholarships, and I couldn’t see myself settling there.

At the same time, Claude Abel made it clear he wanted to secure the future of the show in Sainte-Marie by building a more structured organization. The reboot edition had been successful thanks to a strong community effort, but the structure was still fragile.

“The goal was clear: stabilize and build something long-term.”

I reached out again and told him I had really enjoyed working in events -especially the human connection-and that I wanted to get more involved. His response was simple: “Okay, but only if you agree to get trained.”

That marked the beginning of my skill-building journey. As a teenager, I never imagined I’d one day earn a master’s degree or study at HEC Paris. But that’s where the path led. I first enrolled in a BTS in client relations and negotiation (NRC). Specialized programs in event management are rare, often centered in Paris, and generally broad in scope.

Here in Sainte-Marie, we’re a small structure. We’re not a big organization, so you have to be able to do a bit of everything—you need to be a true Swiss Army knife. My partner, who followed a similar academic path, once worked in events at Orange. There, every role was segmented, every task assigned to a specific team. She handled only communications, within a department of five or six people. It was the complete opposite of how we operate here.

So I needed a 360-degree approach. Claude Abel never told me I had to go all the way to a master’s, but if I was going to take on a cross-functional role, I needed solid skills: technical, commercial, and managerial.

A bachelor’s degree in communications, with a focus on advertising, gave me a broader perspective. That was followed by a master’s in management, business, economics, and law, and then a second master’s in marketing and event management. That was in 2017, if I’m remembering correctly.

The professionalization of the event also came with an institutional shift. How did that structure evolve?

At the time, Mineral & Gem was directly managed by the town hall. But that setup relied on a very rigid legal framework. Every fee had to be approved by vote. For example, when an exhibitor paid in U.S. dollars and the bank converted the transfer into euros, even a few cents’ difference due to fees could become an issue. Multiply that by 300 or 400 transfers, and it added up. Under a municipal structure, pricing is fixed, with no flexibility. So for every tiny variation, even one cent, a separate council resolution was required.

As a result, municipal council meetings were constantly flooded with technical accounting issues related to the event. The same happened in 2014 during the launch of the Jules-Simon site: the initial pricing model didn’t work well, so a discount was introduced. But again, each adjustment had to be voted on, exhibitor by exhibitor. It was no longer sustainable.

That’s why, in 2015, local officials decided to create a SPL (Local Public Company), a structure now widely used in France. It functions much like a private company, except its shareholders are local authorities. In our case, the board is made up of seven elected officials: four from Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines and three from the local council community.

“This new legal status helped anchor the event more securely in the region.”

Today, we operate under a public service delegation agreement, through which the city of Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines officially entrusts us with organizing Mineral & Gem. The SPL status also prohibits us from working outside our defined territory -in other words, we’re limited to the city and the local community. This means the event can’t be relocated to Colmar or anywhere else.

With this new structure in place, Claude Abel became CEO. But, as with any public entity, there’s an age limit for holding both president and CEO roles. In 2019, he reached that threshold. He remained president, but a new CEO had to be appointed. That’s when Jean-Patrice stepped in to lead the SPL, with the mission of managing the transition until his retirement in 2022, when he would hand things over to me.

To prepare for that, I completed a program at HEC Paris between 2019 and 2020, focused on managing this kind of organization. The name of the course was fitting: “Leading an Organization in a changing environment.” Ironically, COVID hit right in the middle of it. At the time, it was almost surreal… but more than anything, that period turned out to be one of the most challenging we’ve ever faced.

Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines and the Val d’Argent have a mining history that spans centuries. How did this heritage give rise to Mineral & Gem, and what are the event’s concrete impacts on the region today?

Mineral & Gem was born here in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines because of that deep-rooted heritage. The area is historically tied to silver mining, with a silver rush in the 17th century and many phases of extraction over time. Within France, Sainte-Marie remains a rich mineralogical region, both scientifically and in terms of cultural heritage.

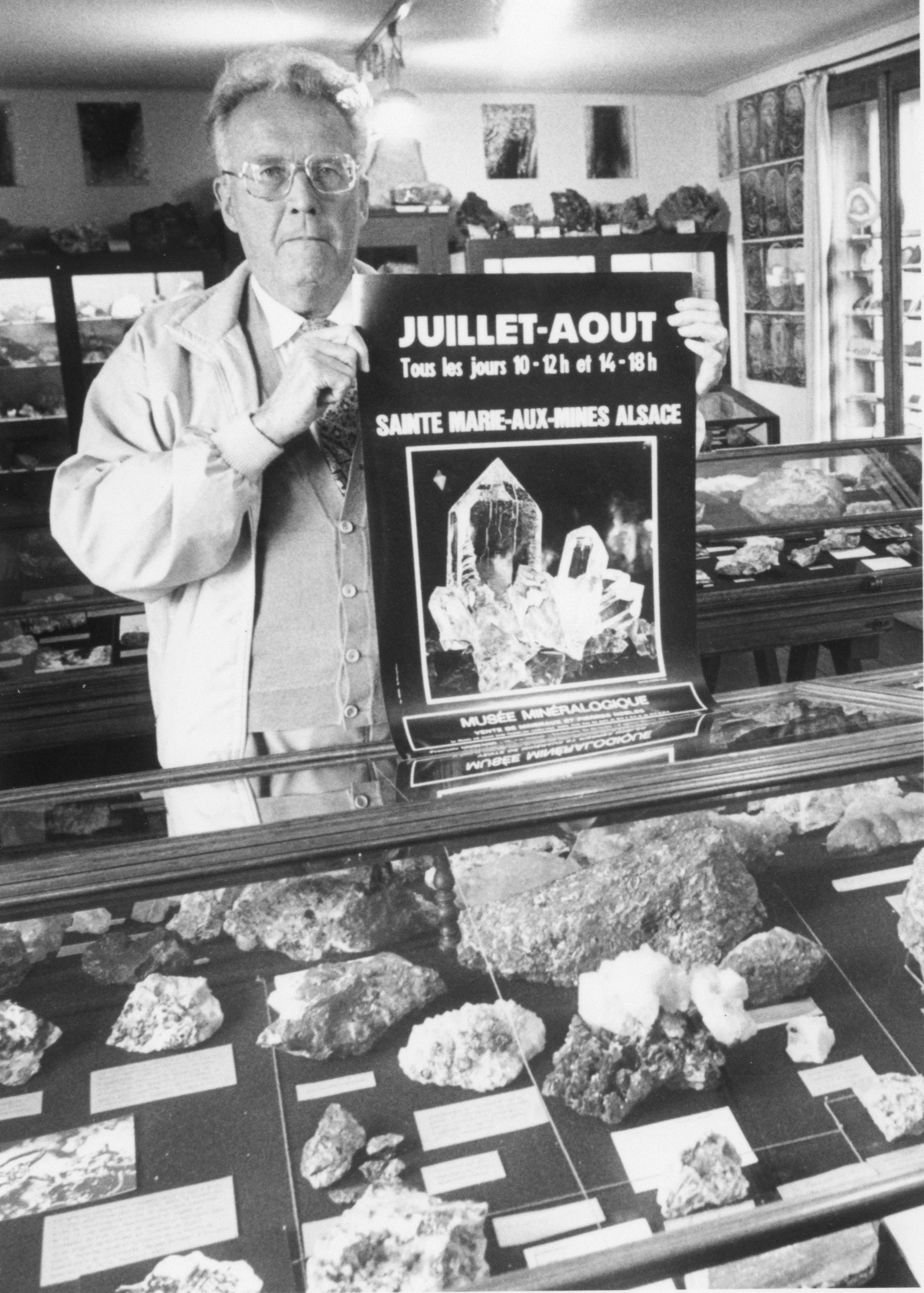

The event first took shape over 60 years ago thanks to François LEHMANN. It gradually developed, then grew significantly in scale under Michel Schwab, who played a major role in expanding its reach, first nationally, then internationally.

One of the things that makes Sainte-Marie so unique is how the event completely transforms the town. It’s something of a UFO compared to other shows. The city center becomes a temporary village -a space entirely reorganized to welcome exhibitors and visitors. Not all residents love it, of course, but it remains a one-of-a-kind moment.

Local nonprofits, on the other hand, benefit significantly. The event mobilizes over 740 volunteers and around 30 associations. Each year, about €40,000 is redistributed to partner organizations. Some manage parking lots, others run food stands or beverage services. In total, their combined revenue can exceed €300,000, with a conversion rate of around 50%, meaning €150,000 goes straight back into their activities.

I remember as a kid, I paid just €10 for a yearlong badminton club membership. That kind of affordability is largely thanks to this financial support. Some associations walk away from the event with €20,000 to €40,000 in earnings, which is huge for groups with just 50 to 150 members.

To give some perspective: I’m currently president of a badminton club in Châtenoy (Bas-Rhin). There, a big event like Slow Up, which brings in 45,000 people in early June, only generates around €1,500 for the club. That gives you an idea of the difference.

During COVID, the absence of the event in 2020 and 2021 was deeply felt, not just by associations, but also by local artisans and restaurants. Mineral & Gem, combined with the Patchwork event, generates over 100,000 overnight stays in the region. That alone shows how significant the economic impact is for the area.

And since local hotel capacity is limited, many exhibitors stay with residents. That human connection creates lasting bonds, as exhibitor turnover is quite low. Some even share meals with their hosts, creating real moments of warmth and connection.

This unique setting, up in the mountains, both indoor and outdoor, at the start of summer, gives the event a truly special atmosphere. Many exhibitors tell us it feels like being on vacation. It’s a feeling we cultivate.

Despite the logistical challenges -distance from train stations, airports, difficult access- we double down on hospitality. It’s our way of meeting those challenges, and it’s also what keeps people coming back. That welcoming spirit already existed in Michel Schwab’s time, but Claude Abel made it a central pillar of our strategy. And even now, we work hard to preserve that atmosphere.

What are the main logistical challenges of hosting over 1,000 exhibitors and more than 42,000 visitors in such a limited geographic area?

The event covers 52,000 square meters of exhibition space, plus another 50,000 square meters dedicated to supporting services, mostly parking. Altogether, nearly 100,000 square meters have to be mobilized every year. If you’ve seen Sainte-Marie outside of the show period, you realize just how massive a transformation this is.

Setup begins in early June with the gradual closure of the « Mineral » and « Gem » zones. Four companies are brought in to install 700 tents, on a very tight schedule. Unlike a convention center, nothing here is standardized: the streets aren’t flat, there are sidewalks, trees, streetlights… all of which must be worked around or temporarily removed.

Before tents can even be installed, the streets need to be weeded, trees trimmed, urban furniture taken down, aerial signage put up, and underground utilities mapped to avoid hitting gas, water, or power lines. Every phase has to fit perfectly into a packed schedule. We also install more than 4 kilometers of crowd-control barriers, implement a temporary traffic plan overnight, and coordinate constantly with public works teams to transform the town center into an event village.

Starting in early May, about 30 people work daily on this transformation. Teardown goes faster: streets reopen on July 4, but everything until then has to be meticulously planned. Each contractor has a precise window for their part. For example, portable restrooms can’t arrive too early (to avoid unnecessary costs), but also not too late (or they’ll delay setup).

The electrical setup is just as intense: we request 27 temporary connections from the national utility company, and over 5 kilometers of cable are laid. We need nearly 5,000 tables. We own 3,000, but the rest have to be rented. Water hookups, roadworks, safety infrastructure, every detail is carefully orchestrated. Concrete security posts have now replaced logs, and are installed all over town for added safety.

Logistics also have to adapt to local life continuing around the event especially the presence of schools. That means creating secure zones and working with extreme care to prevent accidents.

This is probably the most delicate part of organizing the event. And for it to work, it requires coordination and above all, a big-picture view.

“The smallest oversight can throw everything off.”

Every year brings unexpected challenges. The goal is to anticipate as many as possible, but some things are simply out of our control. In 2022, for example -the year after COVID- the pressure was especially intense. All our key partners had been weakened: security, cleaning, tent installation… These sectors often rely on short-term contracts and had little or no support during the pandemic. Many workers had switched careers, and when things started back up, everything came online at once. The result? Daily uncertainty: about equipment, staffing… everything. Internally, the stress was enormous but externally, we had to make it look seamless.

One vivid example: the day before the trucks were scheduled to arrive, a tent installer drilled just 30 cm away from a high-voltage line. The impact wasn’t immediate, but by 9 p.m., we realized a phase of the downtown electrical grid had been hit. Some houses had power in the living room but not in the kitchen.

By 10:30 p.m., the utility company had dispatched a specialized team. Several tents had to be taken down, the pavement opened, and emergency repairs made. The operation wrapped up at 4 a.m. And by 6 a.m., the first trucks were already rolling in.

The year is punctuated by two major events. How does your team adapt to these key moments—between operational phases and planning periods?

From mid-May until the event opens, we’re fully in operational mode. It’s an intense period, filled with last-minute issues that often require quick, on-the-spot decisions.

Our team includes ten people, but not everyone works full-time on Mineral & Gem year-round. Depending on the time of year, each team member focuses on a specific event. During Mineral & Gem, the entire team shifts its focus to the mineral show. The same goes for the European Patchwork Meeting, everyone transitions to that event when the time comes.

Outside those peaks, responsibilities are divided based on each person’s expertise. For example, Mireille and Anaïs manage Mineral & Gem exhibitors, while Adeline handles those for Patchwork. Oriane, who oversees exhibitions for Mineral, supports other events as needed, while Marion leads the artistic programming for Patchwork.

Each event has its own timeline. Once Mineral & Gem wraps up, teardown takes about two weeks. After that, the team takes a few days off before diving into Patchwork preparations which, while still important, is less demanding from a logistics standpoint.

Soon after that comes The Munich Show, which keeps us busy again before we head into a quieter end of the year. That’s when we finally have time to step back: analyze what worked, gather feedback, and think about what we want to improve moving forward.

The pace is definitely uneven. To me, it feels like a yo-yo between high-stress periods and calmer phases better suited for reflection and planning.

You mentioned the complexity of managing such a dynamic event. In your opinion, what human or leadership qualities are essential for this role?

Of course, a certain level of rigor is necessary but without falling into overly rigid methods. I’d say I’m demanding when it comes to process, but I try to stay flexible. And above all, I’m lucky to rely on a strong, tight-knit, and genuinely dependable team.

That said, let’s be honest: you can’t just hand over the reins of an event like Mineral & Gem to anyone. It’s a complex system, where even the smallest disruption can have ripple effects. When you’re deep in the heart of the organization, you can feel the moment everything shifts, when the machine is in motion and total control becomes impossible. It’s almost tangible.

Unexpected issues are inevitable. The key is learning how to handle them. Personally, I’ve taught myself to keep things in perspective. Some members of the team are more affected by the daily ups and downs -and that’s not a weakness- but it can make crisis management tougher. You have to know how to prioritize, take a step back, and accept a certain level of uncertainty.

Another essential quality is vigilance. You never really know where the next problem will come from. So you have to stay alert at all times, while still being able to make quick decisions and gauge the right response. For me, compartmentalizing helps. That’s how I stay grounded.

In June, I rack up close to 48 hours of phone calls. During the setup phase, I’m in constant contact (whether by phone or walkie-talkie) from morning to night. The demands are nonstop, and it’s simply not possible to be everywhere at once.

That’s why I don’t consider myself indispensable to the organization. Even if my colleagues might say otherwise, I see myself more as a wild card or a conductor: I’m not playing every instrument, but I’m keeping the whole orchestra in sync.

“My role today is to manage all the incoming information, respond to requests, and resolve problems as they arise, constantly.”

As you mentioned, every edition brings its share of surprises. How have you adapted Mineral & Gem to new constraints, and what challenges still lie ahead?

Since the pandemic, the constraints we face have continued to evolve. New regulations appear every year. On the visitor and exhibitor side, we haven’t seen major shifts in expectations or behaviors. But the most noticeable change has come from local residents: acceptance has become more difficult. Some neighbors, who don’t directly benefit from the event, are inconvenienced by it without seeing any clear return. We have to take that into account.

Since COVID, we’ve stepped up our communication and engagement with residents, especially those who live within the event perimeter. Strengthening this connection with the local community has become a core part of our organizational strategy.

The main challenge remains the long-term sustainability of the event. Mineral & Gem is a unique format -it doesn’t follow the usual industry playbook. That uniqueness is its strength, but also its vulnerability. It doesn’t take much to throw off the balance. Regulatory changes like new Vigipirate (anti-terrorism) measures or stricter fire and safety codes for public events (ERP standards), can force major adjustments. A reduced capacity limit or tighter security requirements could mean rethinking certain zones or even reworking entire sections of the show.

Logistically, the challenges are just as significant. The nonprofit network remains a pillar of the event, but recruiting volunteers has become harder. In 2022, just ten days before opening, we were still missing associations to staff two of the entrance points in the « Mineral » zone. And without volunteers, certain essential roles simply can’t be filled.

Our service providers are facing similar issues. Some sectors are still struggling to hire. In 2023, we had to find 400 tents on short notice. Every company we contacted (in France, Germany, Spain, Belgium) turned us down. We had to make do with what we could get.

What works one year isn’t guaranteed the next. Before the pandemic, tent rentals cost us €200,000. For the same equipment today, the price has doubled to €400,000. We absorbed that increase by reducing our margins. It was out of the question to pass the full cost on to exhibitors. We know that coming to Sainte-Marie already requires significant logistical effort, and we want to maintain a fair balance. We had to find the right balance.

It’s also important to remember that Mineral & Gem is currently the only profitable event operated by our SPL. Other events -like Patchwork or Mode & Tissus– are structurally in the red. So the financial health of the entire organization largely depends on the success of Mineral & Gem. This year, we applied a modest price increase for exhibitors. With 1,000 of them, even a small adjustment helps generate a bit of extra margin.

But we have to stay vigilant. Nothing is ever guaranteed.

This year, Mineral & Gem celebrated its 60th edition. What new challenges do you hope to tackle, and what’s your vision for the future?

To me, one of the key challenges for the future of Mineral & Gem is preserving its current format. We need to make sure the event doesn’t gradually expand informally beyond its official schedule. It’s a delicate balance: we’re already seeing more buyers arrive before the show officially opens to the public. If an unaccredited visitor tries to enter the site on a Tuesday, for example, they’ll be denied access -unless they have VIP status or are invited by an exhibitor. If this trend continues, it could eventually undermine the momentum and energy of the official opening days.

We’re keeping a close eye on that, especially when looking at events like Tucson, where the spread-out timeline has significantly diluted attendance intensity. That kind of dispersion, coupled with rising costs, puts the financial stability of such events at risk. Here in Sainte-Marie, we’ve always chosen to maintain accessibility, without automatically passing on cost increases to attendees. By contrast, some competing shows have adopted aggressive pricing strategies, charging for early entry or adding extra service fees.

Another advantage we have is our local setting. Even though some hotels raise their prices during the show, it’s still possible to find reasonably priced accommodations either locally or with residents. For comparison, our most recent trip to Tucson made the trend quite clear: we paid nearly 50% more than the previous year for a smaller space and a shorter stay.

We also benefit from how geographically concentrated the event is. The idea of spreading out to multiple sites has come up several times especially during the pandemic. We studied the possibility of directing traffic to nearby towns like Lièpvre or Rombach-le-Franc to comply with attendance caps.

“That model brings far more logistical complexity: transportation, parking, security, technical management… And these alternate sites can’t be marketed under the same terms.”

So our strategy is to protect the current setup while staying alert to its evolution. One area we need to improve is youth outreach. Since COVID, we’ve had to suspend our educational programs for young audiences, and various constraints have delayed their return. The renovation of the Lycée Alberg, in particular, has deprived us of its courtyard, which we used to host children’s activities. We’ve relocated some zones to compensate, but that came at the cost of parking space. As a result, the kids’ village had to be canceled. Yet reaching out to schools and fostering science education remain top priorities for us.

As for digital tools, we’ve had internal discussions, but chose not to pursue a radical pivot in that direction. The market has evolved independently, with platforms like Catawiki and social networks where exhibitors now organize themselves. During the 2024 edition, I was struck by the number of Asian visitors live-streaming the show on various platforms.

This is a deliberate choice. I firmly believe the strength of Mineral & Gem lies in the physical experience: seeing, touching, connecting. That tangible relationship with objects and people is essential. Visitors don’t come just for the minerals; they come for the conversations, the encounters, the human connection. That relational foundation is central to our identity, and we’re deeply committed to preserving it.

At the same time, we’re continuing to raise the quality of our exhibitions. That remains one of our highest priorities.

In a perfect world, with no budget or logistical constraints, what would your dream version of Mineral & Gem look like?

In an ideal world, free from budget limits, logistical hurdles, or regulatory constraints, Mineral & Gem would be fully integrated into the urban and natural landscape. The event would blend seamlessly into its surroundings while showcasing every iconic spot in town.

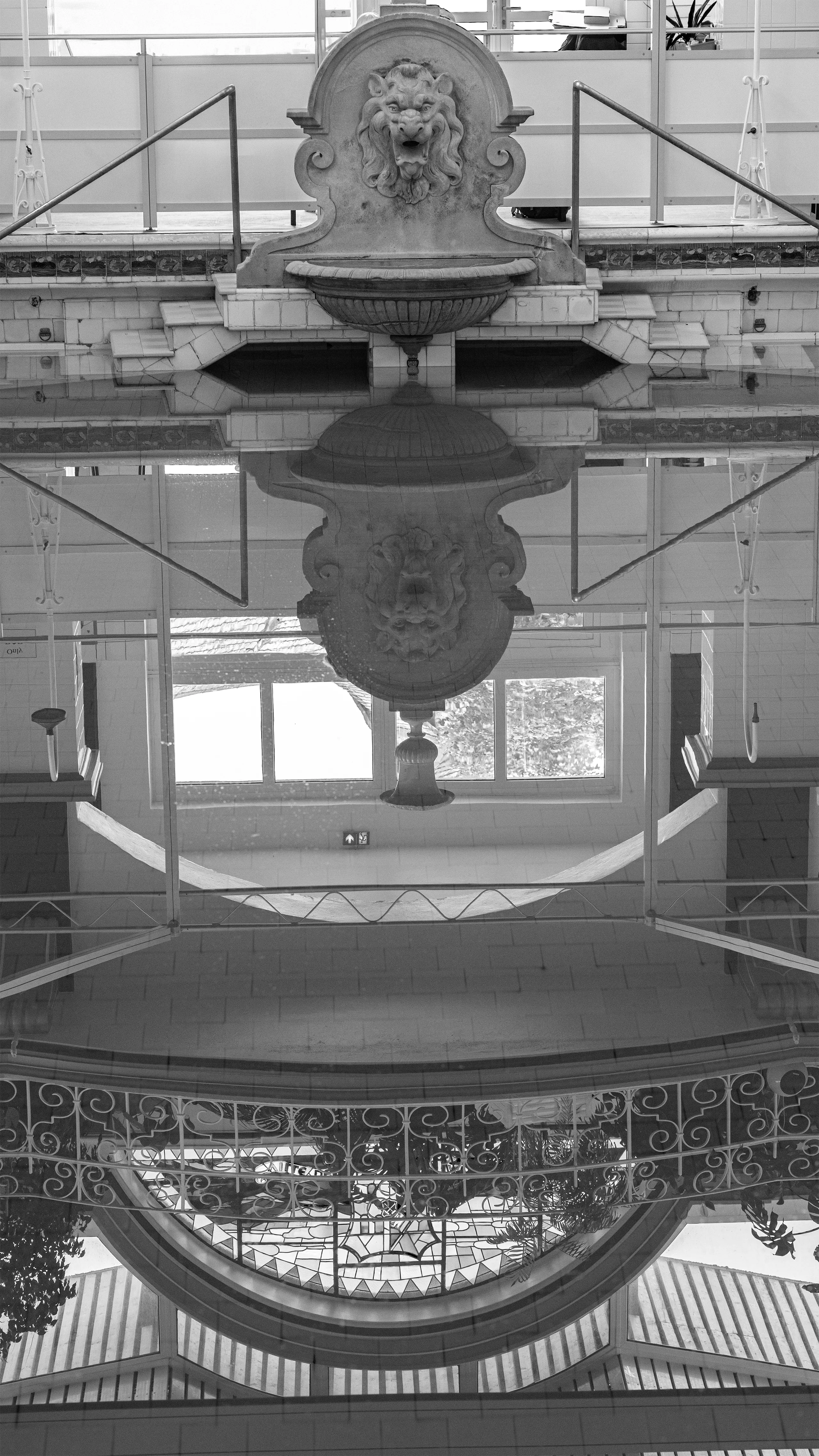

We’d take full advantage of Sainte-Marie’s most prestigious venues like the theater, transforming them into five-star-worthy spaces hosting top-tier exhibitors. I’ve always had this image in mind: turning the swimming pool into a walkable glass-floored space, with a dramatic, immersive scenography. Picture a giant flying reptile suspended from the ceiling. We’ve looked into this idea, but under current conditions, it’s simply not feasible.

The goal would be to place exhibitors in exceptional settings, in a way that feels natural and elegant, with custom designs that integrate beautifully into each site. And of course, in this perfect version, we’d control the weather too: no rain, no heatwaves, no unexpected storms.

Because the weather, truthfully, is one of the biggest wild cards we face. Some years, a sudden storm has forced us to close early by an hour. On other occasions, like during an official heat advisory, authorities have canceled all school outings. And while it’s never happened, we always have to prepare for the possibility of an extreme weather event.

The same goes for safety regulations. After the Nice attacks, for example, the Vigipirate plan required the installation of concrete barriers around the Jules-Simon park. These are heavy but necessary adjustments. In a perfect world, all of that would be anticipated, absorbed, and implemented seamlessly with both efficiency and grace.

Is there someone you’d love to see interviewed as part of this series? And if so, what question would you ask them?

I think it would be fascinating to interview someone who’s still alive and has had a mineral named after them. It’s a bit of an ego thing, sure, but I’ve always thought that’s the ultimate grail.

If I could ask just one question, it would be: “What does it actually feel like to see your name become a scientific reference?” That must be such a singular emotion, being literally etched into the history of mineralogy.

It reminds me of Jean-Claude Leydet. He once had this beautiful idea: a “family photo” gathering everyone alive who has a mineral named after them. Sadly, he’s no longer with us, but that vision and his passion still resonate with many of us today.